- Sánchez Graells, Albert, Rejection of Abnormally Low and Non-Compliant Tenders in EU Public Procurement: A Comparative View on Selected Jurisdictions (April 11, 2013). European Procurement Law Series, Vol 6 (forth). http://ssrn.com/abstract=224859

Cheaters beware: GC enforces strict #suspension rules in EU #publicprocurement (T-87/11)

Without prejudice to the application of penalties laid down in the contract, candidates or tenderers and contractors who have made false declarations, have made substantial errors or committed irregularities or fraud, or have been found in serious breach of their contractual obligations may be excluded from all contracts and grants financed by the Community budget for a maximum of five years from the date on which the infringement is established as confirmed following an adversarial procedure with the contractor.That period may be extended to 10 years in the event of a repeated offence within five years of the date referred to in the first subparagraph (emphasis added).

the applicant has seriously failed to meet its contractual obligations. In addition, it should be recalled that the Court of Auditors, which is one of the institutions of the Union, is dedicated to examining the legality and regularity of revenue and expenditure of the Union and any organ or body created by the EU and to ensure their sound financial management (Article 287, second subparagraph, TFEU). Particularly in view of these missions and the severity of the deficiencies attributable to the applicant, it should be considered that the latter, by his conduct undermined the image of the Court of Auditors and the European Union (T-87/11, para 81, own translation from French).

If you fine me, I have the right to appeal ~ even if someone else foots the bill (C-652/11)

I think that the Mindo Judgment must be welcome and the CJEU has rightly quashed the prior GC ruling, which was basically relying on a set of 'factual' assumptions that were too far fetched. As the CJEU clearly emphasises, the GC erred in law in assuming that, by simply waiting to claim, Mindo's co-debtor had waived its right to seek reimbursement of the fine (particularly in a scenario where there was a pending appeal and, on top of that, Mindo had filed for bankruptcy and was under administration in accordance with Italian law--which justify the 'wait and see' strategy adopted).

I think that the Mindo Judgment must be welcome and the CJEU has rightly quashed the prior GC ruling, which was basically relying on a set of 'factual' assumptions that were too far fetched. As the CJEU clearly emphasises, the GC erred in law in assuming that, by simply waiting to claim, Mindo's co-debtor had waived its right to seek reimbursement of the fine (particularly in a scenario where there was a pending appeal and, on top of that, Mindo had filed for bankruptcy and was under administration in accordance with Italian law--which justify the 'wait and see' strategy adopted).CJEU strengthens #EULaw on #food #information: more #disclosure in the #consumers' interest

35. In so far as a foodstuff is unacceptable for human consumption and accordingly unfit therefor, it does not fulfill the food safety requirements under Article 14(5) of Regulation No 178/2002, and is, in any event, such as to prejudice the interests of consumers, the protection of whom, as stated in Article 5 of that regulation, is one of the objectives of food law.36. It follows from the above that, where food, though not injurious to human health, does not comply with the aforementioned food safety requirements because it is unfit for human consumption, national authorities may, as provided under the second subparagraph of Article 17(2) of Regulation No 178/2002, inform the public thereof in accordance with the requirements of Article 7 of Regulation No 882/2004 (emphasis added).

#GAO reports that there is scope for more competition in #US Defense #procurement

Stubborn #publicprocurement #aggregation: #Madrid City Council insists in tendering macrocontracts

Last November, the City Council of Madrid tendered a single contract for waste collection. The contract was intended to aggregate and consolidate the prior 13 separate outstanding contracts, which would have given the awardee responsibility for waste collection throughout the municipality, with the only exception of the city centre (for some reason). The contract was worth €542 million and the Council expected to save €11 million in the 8 years it would last.

The tender was a massive failure. Current contractors opposed a contract consolidation strategy that would exclude most of them due to their limited size and waste processing capacity. There was a strike to protest a change of waste management strategy that trade unions anticipated would cut jobs. More generally, the financial structure of the contract was considered nonviable by experts. In fact, only the largest incumbent (FCC) submitted a bid, which was disqualified because it exceeded the maximum bidding price by 34%. The tender was declared deserted and prior contracts were extended.

The situation is very unsatisfactory, as contract extension is not without problems. Contractual conditions designed several years ago are no longer adjusted to reality. Waste collection is now bad business, as the economic crisis has generated a reduction of household waste (at least, that is environmentally encouraging) and that means reduced pay for waste collection companies, since they are paid by collected ton of waste. FCC itself has announced job cuts, which the Madrid City Council opposes on the basis that the number of employees is a contract compliance clause the contractor cannot breach, despite the contract having been extended beyond its original duration and the conditions having changed significantly (an scenario that actually may make judges side with the contractor if this issue got to court). Trade unions are again promoting a new strike to protest the situation, which will result in no waste collection in Madrid for an indefinite period starting on the 15th of April.

Cynically, we could say that Madrid city is facing a waste wave if the situation does not get sorted out soon. And the prospects are gloomy. According to today's press releases, the City Council has decided that, if you cannot solve a problem, better make it bigger.

The Council has stubbornly decided to go deeper and broader in its (failed) contractual consolidation strategy and to tender a single macrocontract to consolidate the 39 outstanding for all public service activities of cleaning and maintenance of public spaces and green areas of the capital. The new service would run for 8 years (with a possible extension for 2 more), and is valued at €2.3 billion. With this new formula, the Council expects savings of 10% of current cleaning and gardening costs (a rough equivalent of €256 million throughout the life of the contract without the extension). Does this sound familiar?

Interestingly enough, the largest players in the cleaning, gardening and maintenance business are the same as in the waste collection side. It do not think it will be anyone's surprise if we hear again that only one or a very limited few of them participate in this second macrocontract, or that they submit financial offers in excess of the (dreamy?) expectations of the Madrid City Council.

Now, the open question is why a city council of one of the largest capitals in the EU insists in a failed strategy for the tendering of local services of such relevance? Are there no better ideas available in their in-house group of experts? Are they so stubborn that they are trying to prove they were right in the prior instance by failing again?

Also, I think that the Madrid experience offers some lessons for other city councils facing similar challenges (ie, the need to find new management strategies for public services that allow them to reduce costs) and that are thinking about contract aggregation and consolidation. I think that the easier one is that you cannot aim to consolidate beyond the size your market structure can reasonably digest. The second one is that you cannot intend to award non-profitable contracts. And, the hardest one, that some creative thinking is needed. Would anyone publish a call for ideas? I would definitely be tempted to contribute.

Avoiding gold plating in the transposition of #EUlaw: A distinctive UK approach?

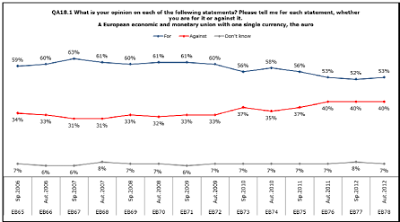

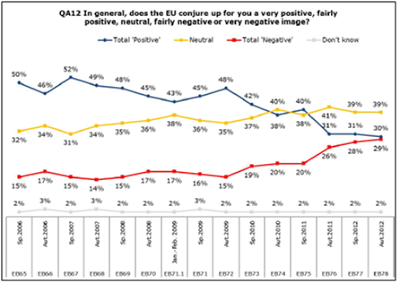

Becoming true #EUcitizens: The only way out of the #crisis (and beyond)?

Source: Standard Eurobarometer 78, December 2012, p. 16.

Source: Standard Eurobarometer 78, December 2012, p. 15.

How #publicprocurement rules seem to be diminishing #competition in #China: A wake up call

The principles of openness and transparency, fair competition, impartiality, and good faith are required to be observed in government procurement. China’s government procurement system provides general rules on competition, transparency, and fairness. However, the implementation of the rules is less than ideal. Insufficient disclosure of information, conflicts of interest, discriminatory treatment of enterprises, excessive prices, and poor quality purchasing have been frequently reported and raised the public’s concern in recent years. The newly released Blue Book of Rule of Law: Annual Report on China’s Rule of Law No. 11 (2013) provides an empirical report on the current state of government procurement.

Data and price comparison results revealed that certain government procured goods can be much more expensive than average market prices. An extreme example mentioned in the report was a desktop computer that was procured at a cost of CNY 98,730 when the average market price for a computer with the same specifications was CNY 2,649. [...] In the end, the prices of 19,020 items were compared. These goods covered 29 product categories such as uninterruptible power systems, laptops, dehumidifiers, printers, and fax machines. The results show that the prices of 15,190 items were higher than the average market prices and that taxpayers had paid an extra CNY 20,743,897.50. On the positive side, the price comparison results show that 68,025 items purchased through the centralised procurement of the Central Government had saved taxpayers CNY 5,543,185. The 68,025 items, covering desktops, workstations, and printers, were chosen from 85,963 records collected for the research.

the report notes that transparency is the foundation of fair competition, impartiality, and good faith. Transparency can effectively facilitate fair competition, deter corruption, and prevent China, the world’s largest procurement market, from turning into the world’s largest market for public corruption.

a substantial body of literature confirms that procurement rules can have a significant negative impact on competitive commercial markets. Procurement rules can, for example, raise new barriers to entry in the commercial marketplace, facilitate collusion in the commercial space, or artificially buoy commercial prices. Federal procurement regulators have not, as a regular matter, assessed those possible impacts in past rulemaking, but sound practice and legal authority, including an executive order, seem to call for such assessments. Assessing procurement rules’ likely impact on competitive markets would be in accord with best practices in rulemaking, and would help ensure that the federal procurement system integrates efficiently, and not disruptively, into the broader economy.

Not worth the paper it is written on? ~ AG on the expectations created by legal advice in #competition (C-681/11) #EULaw

Apparently, the members of the [cartel] wrongly considered that they had stayed ‘on the safe side’, as far as European Union law was concerned, by restricting the geographical scope of their cartel to Austria alone. In the light of the case-law of the European Union courts and the administrative practice of the European Commission, there is no doubt that that legal opinion was objectively incorrect. However, it is unclear whether the infringement of the prohibition of cartels under EU law can also be attributed subjectively to the undertakings concerned. In other words, it must be examined whether the undertakings participating in the [cartel] culpably infringed the prohibition of cartels under EU law (Opinion in C-681/11, at para 36, emphasis in the original, footnotes omitted).

44. According to the principle of nulla poena sine culpa, an undertaking may be held responsible for a cartel offence which it has committed on a purely objective basis only where that offence can also be attributed to it subjectively. If, on the other hand, the undertaking commits an error of law precluding liability, an infringement cannot be found against it nor can it form the basis for the imposition of penalties such as fines.45. It should be stressed that not every error of law is capable of precluding completely the liability of the undertaking participating in the cartel and thus the existence of a punishable infringement. Only where the error committed by the undertaking regarding the lawfulness of its market behaviour was unavoidable – sometimes also called an excusable error or an unobjectionable error – has the undertaking acted without fault and it cannot be held liable for the cartel offence in question.46. Such an unavoidable error of law would appear to occur only very rarely. It can be taken to exist only where the undertaking concerned took all possible and reasonable steps to avoid its alleged infringement of EU antitrust law.47. If the undertaking concerned could have avoided its error regarding the lawfulness of its market behaviour – as is often the case – by taking adequate precautions, it cannot escape any penalty for the cartel offence committed by it. Rather it will be liable at least for a negligent infringement, which, depending on the seriousness of the questions of competition law involved, may (but not must) lead to a reduced fine.48. It is necessary to assess whether the error of law committed by an undertaking participating in a cartel was avoidable or unavoidable (objectionable or non-objectionable) on the basis of uniform criteria laid down in EU law, so that uniform conditions in respect of EU substantive competition law apply to all undertakings operating in the internal market (‘level playing field’) (Opinion in C-681/11, at paras 44 to 48, bold emphasis in the original, underlined added, footnotes omitted).

57. [...] obtaining expert legal advice has a completely different importance in the system under Regulation No 1/2003 than was the case in the system under Regulation No 17. Consulting a legal adviser is now often the only way for undertakings to obtain detailed information about the legal situation under antitrust law.58. It is not acceptable, on the one hand, to encourage undertakings to obtain expert legal advice but, on the other, to attach absolutely no importance to that advice in assessing their fault in respect of an infringement of EU antitrust law. If an undertaking relies, in good faith, on – ultimately incorrect – advice provided by its legal adviser, this must have a bearing in cartel proceedings for the imposition of fines.59. In particular, the purely civil liability of a lawyer for incorrect legal advice given by him does not, contrary to the view taken by the European Commission, constitute adequate compensation in itself. Civil recourse by a client against his lawyer is generally subject to considerable uncertainty and, moreover, cannot dispel the condemnation (‘stigma’) associated with the imposition of cartel – i.e. quasi-criminal – penalties against the undertaking.60. Of course, obtaining legal advice cannot exempt an undertaking from all individual responsibility for its market behaviour and for any infringements of European competition law. The opinion of a lawyer can never give carte blanche. Otherwise, this would open the way to the production of opinions tailored to the interests of the undertaking and the power to give official negative clearance abolished by Regulation No 1/2003 would be transferred de facto to private legal advisers, who do not have any legitimacy in that regard.61. In accordance with the fundamental objective of the effective enforcement of European competition rules, any expectations on the part of an undertaking created by legal advice may be recognised as the basis for an error of law precluding liability only where, in obtaining that legal advice, certain minimum requirements were complied with, which I will describe briefly below.Minimum requirements in obtaining legal advice62. The basic condition for taking into consideration the legal advice obtained by an undertaking is that the undertaking relied in good faith on that advice. Protection of legitimate expectations and good faith are closely related. If the facts justify the assumption that the undertaking relied on a legal opinion against its better judgment or that the report was tailored to the interests of the undertaking, the legal advice given is irrelevant from the very outset in assessing fault for an infringement of the rules of European competition law.63. Furthermore, the following minimum requirements apply to obtaining legal advice, in respect of which the undertaking concerned itself bears the risk and responsibility for compliance.64. First of all, the advice must always be obtained from an independent external lawyer. [...]65. Second, the advice must be given by a specialist lawyer, which means that the lawyer must be specialised in competition law, including European antitrust law, and must also regularly work for clients in this field of law.66. Third, the legal advice must have been provided on the basis of a full and accurate description of the facts by the undertaking concerned. If an undertaking has given only incomplete or even false information to the lawyer consulted by it regarding circumstances which originate from the area of responsibility of the undertaking, the opinion of that lawyer cannot have an exculpating effect in cartel proceedings in relation to any error of law.67. Fourth, the opinion of the consulted lawyer must deal comprehensively with the European Commission’s administrative and decision-making practice and with the case-law of the European Union courts and give detailed comments on all legally relevant aspects of the case at issue. An element which is not expressly the subject-matter of the legal advice but may possibly be inferred implicitly from it cannot form the basis for recognition of an error of law precluding liability.68. Fifth, the legal advice given may not be manifestly incorrect. No undertaking may rely blindly on legal advice. Rather, any undertaking which consults a lawyer must at least review the plausibility of the information provided by him.69. Of course, the diligence expected of an undertaking in this regard depends on its size and its experience in competition matters. The larger the undertaking and the more experience it has with competition law, the more it is required to review the substance of the legal advice obtained, especially if it has its own legal department with relevant expertise.70. In any event, every undertaking must be aware that certain anti-competitive practices are, by their nature, prohibited, and in particular that no one is permitted to participate in ‘hardcore restrictions’, for example in price agreements or in agreements or measures to share or partition markets. Furthermore, large, experienced undertakings can be expected to have taken note of the relevant statements made by the European Commission in its notices and guidelines in the field of competition law.71. Sixth, the undertaking concerned acts at its own risk if the legal opinion obtained by it shows that the legal situation is unclear. In that case, the undertaking is at least negligent in accepting that by its market behaviour it infringes the rules of European competition law.72. Admittedly, in the light of the minimum requirements I have just proposed, the value of legal opinions given by lawyers is slightly diminished for the undertakings concerned. However, this is inherent in the system created by Regulation No 1/2003 and is also no different in conventional criminal law; in the final analysis, any undertaking is itself responsible for its market behaviour and bears the risk for infringements of the law it commits. Absolute legal certainty cannot be secured by obtaining legal advice from a lawyer. However, if all the abovementioned minimum requirements are satisfied, an error of law precluding liability can be taken to exist where the undertaking concerned has relied in good faith on an opinion from its legal adviser.73. It should be added that a lawyer who, by delivering opinions tailored to the interests of an undertaking, becomes an accomplice in the undertaking’s anti‑competitive practices will have to contend with not only consequences under the rules of civil law and of professional conduct, but may possibly also himself be subject to penalties imposed in cartel proceedings (Opinion in C-681/11, at paras 57 to 73, underlined added, footnotes omitted).

US GAO report on the use of small business and other preferences in the acquisition of goods

The US GAO has published an interesting report on the Army's and Defense Logistics Agency's Approach for Awarding Contracts for the Army Combat Shirt.

The US GAO has published an interesting report on the Army's and Defense Logistics Agency's Approach for Awarding Contracts for the Army Combat Shirt. With a little help from my friends: AG Jääskinen supports flexible interpretation of rules on reliance on third party capabilities in #publicprocurement

31. This argument is further supported by analysis of the objectives of Articles 47(2) and 48(3) of Directive 2004/18. According to the Court, one of the primary objectives of the public procurement rules of the European Union is to attain the widest possible opening‑up to competition, and that it is the concern of European Union law to ensure the widest possible participation by tenderers in a call for tenders.32. The objective of widest possible opening‑up to competition is regarded not only from the interest in the free movement of goods and services, but also in regard to the interest of contracting authorities, who will thus have greater choice as to the most advantageous tender. Exclusion of tenderers based on the number of other entities participating in the execution of the contract such as allowing only one auxiliary undertaking per qualitative criteria category does not allow for a case by case evaluation, thus actually reducing the choices of the contracting authority and affecting effective competition.33. Another objective of the public procurement rules is to open up the public procurement market for all economic operators, regardless of their size. The inclusion of small and medium‑sized enterprises (SMEs) is especially to be encouraged as SMEs are considered to form the backbone of European Union economy. The chances of SMEs to participate in tendering procedures and to be awarded public works contracts are hindered, among other factors, by the size of the contracts. Because of this, the possibility for bidders to participate in groups relying on the capacities of auxiliary undertakings is particularly important in facilitating the access to markets of SMEs. (AG in C-94/12 at paras 31 to 33, emphasis added).

#Decency in #publicprocurement could take us out of the #crisis: or how #corruption is making us bleed out

One more #publicprocurement Judgment in the Evropaïki Dynamiki Saga (T-9/10)

It should also be borne in mind that the requirements to be satisfied by the statement of reasons depend on the circumstances of each case, in particular the content of the measure in question, the nature of the reasons given and the interest which the addressees of the measure, or other parties to whom it is of direct and individual concern, may have in obtaining explanations (see Case C‑367/95 P Commission v Sytraval and Brink’s France [1998] ECR I‑1719, paragraph 63 and case-law cited, and Case T‑465/04 Evropaïki Dynamiki v Commission, paragraph 49) (emphasis added).

the Commission considers that it provided a statement of reasons exceeding that laid down in Article 100(2) of [the Financial Regulation] by informing the applicant of the reasons why its tender had been rejected as well as providing the scores obtained by the tenderers at the award stage, even though the applicant had not passed the selection phase (T-9/10 at para. 24, emphasis added).

The Future of European Legal Education -- Comment on Maduro's views

So far European Community law has been conceived mainly as 'black-letter law' [...] it is time to draw upon perspectives from other social sciences and to move in new directions. We must place European Community law in its social, economic and political context. Only in this way can we achieve the deeper and broader understanding—both practical and theoretical—of European Community law [F Snyder, New Directions in European Community Law (Law in Context) 30 (2nd edtn. 1990)].

These changes [derived from increased global economic and social integration] are bound to challenge not only the content of the law but also how it needs to be taught. This context of legal pluralism and legal miscegenation requires different hermeneutics and the interaction between legal cultures, which is triggered by the Europeanisation of the law, will confront each national legal culture with many of its unarticulated assumptions. Change in what you study is often the fastest way to break path-dependencies on how you study (p. 456).

Why is #competition law so special? Or how #leniency will kill private #damages actions (AG C-536/11)

36. In my opinion it is inarguable that such proceedings [ie damages actions based on infringement of EU competition law] are comparable to either ordinary civil or criminal procedures, given that neither is concerned with the protection of leniency programmes or other specific features of public law proceedings in the context of enforcing competition policy (emphasis added).

51. […] subjecting access to public law competition judicial files to the consent of the infringer of the competition rules amounts to a significant deterrent of the exercise to a right to claim civil damages for breach of EU competition law. The Court has ruled that if an individual has been deterred from bringing legal proceedings in good time by the wrong-doer, the latter will not be entitled to rely on national procedural rules concerning time limits for bringing proceedings. I can see no reason for confining the application of this principle to limitation periods, and would advocate its extension to onerous rules of evidence that have an analogous deterrent effect. I would further query the compliance of remedies that deter enforcement of EU law rights with Article 19(1) TEU (footnotes omitted, emphasis added).

55. Article 47 [of the Charter of Fundamental Rights] is also relevant to the case to hand because it guarantees the fairness of hearings, which serves to protect the interests of the undertakings that have participated in the cartel. In my opinion, access by third parties to voluntary self-incriminating statements made by a leniency applicant should not in principle be granted. The privilege against self-incrimination is long established in EU law, and it is directly opposable to national competition authorities that are implementing EU rules.56. It is true that leniency programmes do not guarantee protection against claims for damages and that the privilege against self-incrimination does not apply in private law contexts. Despite this, both public policy reasons and fairness towards the party having given incriminating declarations within the context of a leniency programme weigh heavily against giving access to the court files of public law competition proceedings where the party benefiting from them has acted as a witness for the prosecuting competition authority (footnotes omitted, emphasis added).

64. [...] from the point of view of proportionality, in my opinion a legislative rule would be more appropriate that provided absolute protection for the participants in a leniency programme, but which required the interests of other participants to a restrictive practice to be balanced against the interests of the alleged victims. [...] Furthermore, in my view and except for undertakings benefiting from leniency (sic!), participation in and of itself in an unlawful restriction on competition does not constitute a business secret that merits protection by EU law (emphasis added).

Las tasas judiciales como límite a la efectividad del Derecho UE: Una razón (más) para su supresión

CJEU prevents competitors from taking the law into their hands (C-68/12)

18 Article 101 TFEU is intended to protect not only the interests of competitors or consumers but also the structure of the market and thus competition as such (Joined Cases C‑501/06 P, C‑513/06 P, C‑515/06 P and C‑519/06 P GlaxoSmithKline Services and Others v Commission and Others [2009] ECR I‑9291, paragraph 63).19 In that regard, it is apparent from the order for reference that the agreement entered into by the banks concerned specifically had as its object the restriction of competition and that none of the banks had challenged the legality of Akcenta’s business before they were investigated in the case giving rise to the main proceedings. The alleged illegality of Akcenta’s situation is therefore irrelevant for the purpose of determining whether the conditions for an infringement of the competition rules are met.20 Moreover, it is for public authorities and not private undertakings or associations of undertakings to ensure compliance with statutory requirements. The Czech Government’s description of Akcenta’s situation is evidence enough of the fact that the application of statutory provisions may call for complex assessments which are not within the area of responsibility of those private undertakings or associations of undertakings.21 It follows from those considerations that the answer to the first and second questions is that Article 101 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that the fact that an undertaking that is adversely affected by an agreement whose object is the restriction of competition was allegedly operating illegally on the relevant market at the time when the agreement was concluded is of no relevance to the question whether the agreement constitutes an infringement of that provision (C-68/12 at paras. 18 to 21, emphasis added).

35 Even if [the first] condition were met [regarding the protection of conditions for healthy competition and, in the broader sense, thus seeked to promote economic progress], the agreement at issue in the main proceedings does not appear to meet the other three conditions – more particularly, the third condition, whereby an agreement must not impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions which are not indispensable to the attainment of the objectives referred to in the first condition laid down in Article 101(3) TFEU. Even if, as stated by the parties to that agreement, the purpose was to force Akcenta to comply with Slovak law, it was for those parties [...] to lodge a complaint with the competent authorities in that respect and not to take it upon themselves to eliminate the competing undertaking from the market. (C-68/12 at para. 35, emphasis added).

US GAO report on interagency contracting: A mirror for centralised purchasing strategies in the EU?

OFPP issued guidance in September 2011 that requires agencies to develop business cases for creating new governmentwide acquisition contracts and multi-agency contracts. The business cases must address three key elements: (1) the scope of the contract vehicle and potential duplication with existing contracts; (2) the value of the new contract vehicle, including expected benefits and costs of establishing a new contract; and (3) the administration and expected interagency use of the contract vehicle.The guidance also requires senior agency officials to approve the business cases and post them on an OMB website to provide interested federal stakeholders an opportunity to review and provide feedback. Feedback is addressed through various channels, including posting written comments through the website and sending letters or memos to stakeholders. According to OFPP, it also conducts follow-up with sponsoring agencies when significant questions are raised during the interagency vetting process, including questions related to potential value or duplication.

OFPP and GSA have taken a number of steps to address the need for better data on interagency contract vehicles. We previously have reported that a lack of reliable information on interagency contracts hampers agencies’ ability to do market research as well as efforts to manage and leverage them effectively. To promote better and easier access to data on existing interagency contracts, OFPP has worked to improve the Interagency Contract Directory, a searchable online database of indefinite delivery vehicles for interagency use created in 2003. [...] Short-term improvements include enhancing the search function and simplifying the presentation of search results, which should aid market research. Potential long-term enhancements include the ability to access vendor past performance information and upload contract documents, such as statements of work, to the system. OFPP officials also noted that this information will be helpful in providing data on the use of interagency contract vehicles, as the database provides information on the amount of obligations against the contracts, and eventually may provide other information such as a notification when contracts not designated for interagency use are being used in that manner.

Latest GC on contract modification in #publicprocurement: Practical difficulties and the need for new rules in the 2013 Directive

69 [...] nor can the argument of the Kingdom of Spain that despite the alteration of certain of the characterizing elements of the services contracted, by keeping the contract initially concluded, the modification of the original contract cannot be considered substantial. As is clear from the case law, in order to ensure transparency of procedures and equal treatment of tenderers, amendments to the provisions of a public contract during its validity constitute a new award of the contract when they have characteristics substantially different from those of the original contract and therefore highlight the willingness of the parties to renegotiate the essential aspects of the contract (see, to that effect, the judgment of the Court of 5 October 2000, Commission / France, C-337/98, ECR p. I-8377, paragraphs 44 and 46, see, by analogy, Pressetext Nachrichtenagentur, paragraph 60 above, paragraph 34).70 The modification of a contract in force may be considered material when it introduces conditions that, had they been included in the initial award procedure, would have allowed the participation of tenderers other than those initially admitted, or would have allowed the selection of a tender other than the initially selected. Also, a modification of an initial contract can be considered substantial when the contract extends largely to works not originally foreseen. An amendment can also be considered substantial when it changes the economic balance of the contract in favor of the contractor in a way that was not foreseen in the terms of the original contract (see, by analogy, Case Pressetext Nachrichtenagentur [C‑454/06, Rec. p. I‑4401] paragraphs 35 to 37).71 In the present case, the technical specifications that were modified cannot be considered ancillary, but of a greater importance, as they relate, in particular, to the implementation of important works (such as the execution false tunnels, a viaduct, deepening of foundations, strengthening of technical armor blocks, extension of drainage works, etc..). Therefore, the Kingdom of Spain cannot claim that the work to be executed remains the one initially designed, ie, the high-speed train line, not that the object of the initial contract remained essentially unaltered. (T-231/11 at paras. 69-71, own translation from Spanish; emphasis added).

Article 72 Modification of contracts during their term1. A substantial modification of the provisions of a public contract or a framework agreement during its term shall be considered as a new award for the purposes of this Directive and shall require a new procurement procedure in accordance with this Directive. In the cases referred to in paragraphs 3, 4 or 5, modifications shall not be considered as substantial.2. A modification of a contract or a framework agreement during its term shall be considered substantial within the meaning of paragraph 1, where it renders the contract or the framework agreement materially different in character from the one initially concluded. In any case, without prejudice to paragraphs 3, 4 or 5, a modification shall be considered substantial where one of the following conditions is met:(a) the modification introduces conditions which, had they been part of the initial procurement procedure, would have allowed for the admission of other candidates than those initially selected or for the acceptance of an offer other than that originally accepted or would have attracted additional participants in the procurement procedure;(b) the modification changes the economic balance of the contract or the framework agreement in favour of the contractor in a manner which was not provided for in the initial contract or framework agreement;(c) the modification extends the scope of the contract or framework agreement considerably to encompass supplies, services or works not initially covered.3. Modifications shall not be considered substantial within the meaning of paragraph 1 where they have been provided for in the initial procurement documents in clear, precise and unequivocal review clauses or options. Such clauses shall state the scope and nature of possible modifications or options as well as the conditions under which they may be used. They shall not provide for modifications or options that would alter the overall nature of the contract or the framework agreement.4. Where the value of a modification can be expressed in monetary terms, the modification shall not be considered to be substantial within the meaning of paragraph 1, where its value does not exceed the thresholds set out in Article 4 and where it is below 10% of the initial contract value, provided that the modification does not alter the overall nature of the contract or framework agreement. Where several successive modifications are made, the value shall be assessed on the basis of the net cumulative value of the successive modifications.5. A modification shall not be considered to be substantial within the meaning of paragraph 1, where the following cumulative conditions are fulfilled:(a) the need for modification has been brought about by circumstances which a diligent contracting authority could not foresee;(b) the modification does not alter the overall nature of the contract;(c) any increase in price is not higher than 50% of the value of the original contract or framework agreement.Contracting authorities shall publish in the Official Journal of the European Union a notice on such modifications. Such notices shall contain the information set out in Annex VI part G and be published in accordance with Article 49.6. Without prejudice to paragraph 3, the substitution of a new contractor for the one to which the contracting authority had initially awarded the contract shall be considered a substantial modification within the meaning of paragraph 1. However, the first subparagraph shall not apply in the event of universal or partial succession into the position of the initial contractor, following corporate restructuring, including takeover, merger, […] acquisition or insolvency, of another economic operator that fulfils the criteria for qualitative selection initially established provided that this does not entail other substantial modifications to the contract and is not aimed at circumventing the application of this Directive.