ⓒ Scott Richard, Liquid painting (2015).

On 20 September 2019, and as part of its ‘Unlocking Public Sector Artificial Intelligence’ project, the World Economic Forum (WEF) published the White Paper Guidelines for AI Procurement (see also press release), with which it seeks to help governments accelerate efficiencies through responsible use of artificial intelligence and prepare for future risks. WEF indicated that over the next six months, governments around the world will test and pilot these guidelines (for now, there are indications of adoption in the UK, the United Arab Emirates and Colombia), and that further iterations will be published based on feedback learned on the ground.

Building on previous work on the Data Ethics Framework and the Guide to using AI in the Public Sector, the UK’s Office for Artificial Intelligence has decided to adopt its own draft version of the Guidelines for AI Procurement with substantially the same content, but with modified language and a narrower scope of some principles, in order to link them to the UK’s legislative and regulatory framework (and, in particular, the Data Ethics Framework). The UK will be the first country to trial the guidelines in pilot projects across several departments. The UK Government hopes that the new Guidelines for AI Procurement will help inform and empower buyers in the public sector, helping them to evaluate suppliers, then confidently and responsibly procure AI technologies for the benefit of citizens.

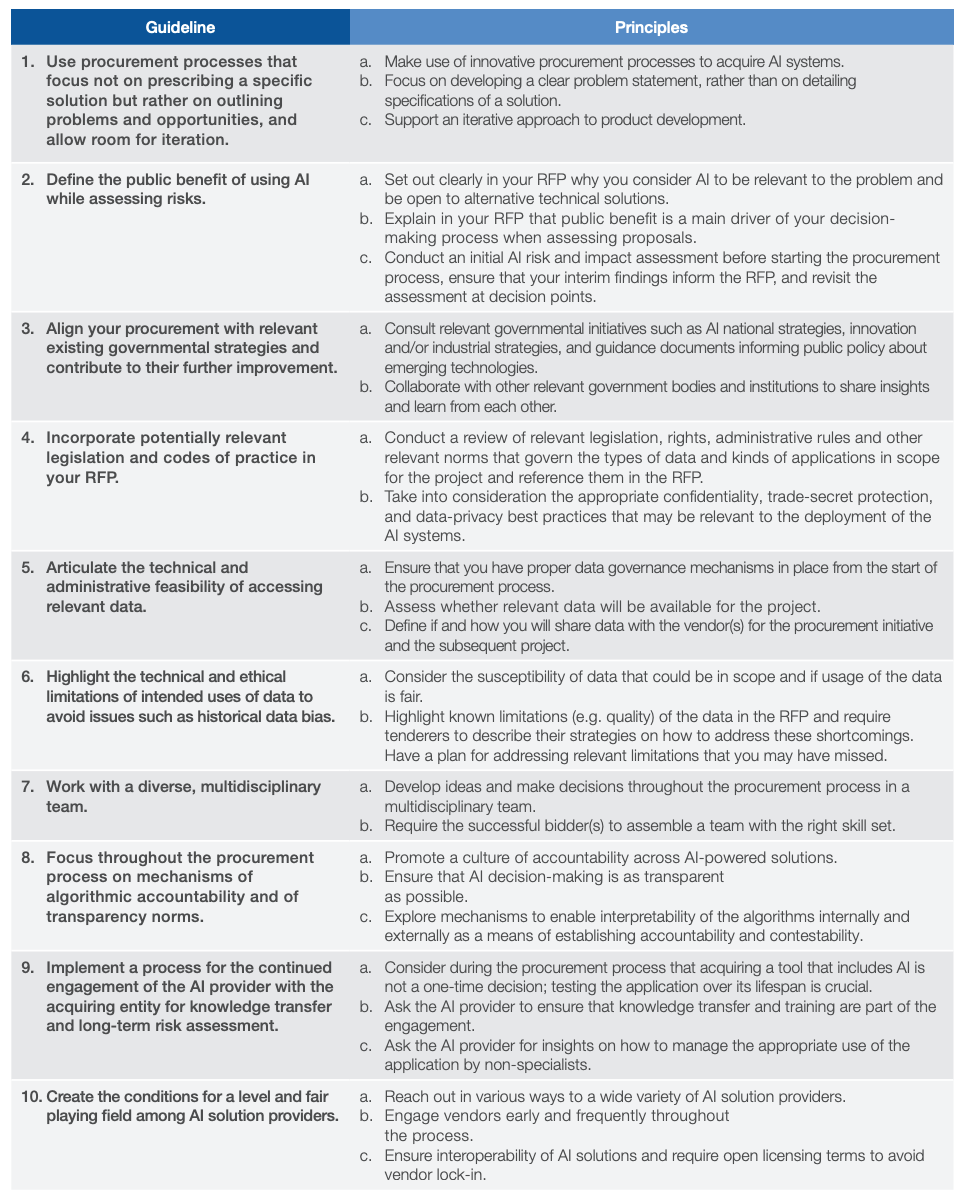

In this post, I offer some first thoughts about the Guidelines for AI Procurement, based on the WEF’s version, which is helpfully summarised in the table below.

Source: WEF, White Paper: ‘Guidelines for AI Procurement’ at 6.

Some Comments

Generally, it is worth being mindful that the ‘guidelines provide fundamental considerations that a government should address before acquiring and deploying AI solutions and services. They apply once it has been determined that the solution needed for a problem could be AI-driven’ (emphasis in original). As the UK’s version usefully stresses, many of the important decisions take place at the preparation and planning stages, before publishing a contract notice. Therefore, more than guidance for AI procurement, this is guidance on the design of a framework for the governance of innovative digital technologies procurement, including AI (but easily extendable to eg blockchain-based solutions), which will still require a second tier of (future/additional) guidance on the implementation of procurement procedures for the acquisition of AI-based solutions.

It is also worth stressing from the outset that the guidelines assume both the availability and a deep understanding by the contracting authority of the data that can be used to train and deploy the AI solutions, which is perhaps not fully reflective of the existing difficulties concerning the availability and quality of procurement data, and public sector data more generally [for discussion, see A Sanchez-Graells, 'Data-Driven and Digital Procurement Governance: Revisiting Two Well-Known Elephant Tales' (2019) Communications Law, forthcoming]. Where such knowledge is not readily available, it seems likely that the contracting authority may require the prior engagement of data consultants that could carry out an assessment of the data that is or could be available and its potential uses. This creates the need to roll-back some of the considerations included in the guidelines to that earlier stage, much along the lines of the issues concerning preliminary market consultations and the neutralisation of any advantages or conflicts of interest of undertakings involved in pre-tender discussions, which are also common issues with non-AI procurement of innovation. This can be rather tricky, in particular if there is a significant imbalance in expertise around data science and/or a shortfall in those skills in the contracting authority. Therefore, perhaps as a prior recommendation (or an expansion of guideline 7), it may be worth bearing in mind that the public sector needs to invest significant resources in hiring and retaining the necessary in-house capacities before engaging in the acquisition of complex (digital) technologies.

1. Use procurement processes that focus not on prescribing a specific solution, but rather on outlining problems and opportunities and allow room for iteration.

The fit of this recommendation with the existing regulation of procurement procedures seems to point towards either innovation partnerships (for new solutions) or dynamic purchasing systems (for existing or relatively off-the-shelf solutions). The reference to dynamic purchasing systems is slightly odd here, as solutions are unlikely to be susceptible of automatic deployment in any given context.

Moreover, this may not necessarily be the only possible approach under EU law and there seems to be significant scope to channel technology contests under the rules for design contests (Arts 78 and ff of Directive 2014/24/EU). The limited appetite of innovative start-ups for procurement systems that do not provide them with ‘market exposure’ (such as large framework agreements, but likely also dynamic purchasing systems) may be relevant, depending on market conditions (see eg PUBLIC, Buying into the Future. How to Deliver Innovation through Public Procurement (2019) 23). This could create opportunities for broader calls for technological innovation, perhaps as a phase prior to conducting a more structured (and expensive) procurement procedure for an innovation partnership.

All in all, it would seem like—at least at UK level, or in any other jurisdictions seeking to pilot the guidance—it could be advisable to design a standard procurement procedure for AI-related market engagement, in order to avoid having each willing contracting authority having to reinvent the wheel.

2. Define the public benefit of using AI while assessing risks.

Like with many other aspects of the guidelines, one of the difficulties here is to try to establish actionable measures to deal with ‘unknown unknowns’ that may emerge only in the implementation phase, or well into the deployment of the solution. It would be naive to assume that the contracting authority—or the potential tenderers—can anticipate all possible risks and design adequate mitigating strategies. It would thus perhaps be wise to recommend the use of AI solutions for public sector / public service use cases that have a limited impact on individual rights, as a way to gain much necessary expertise and know-how before proceeding to deployment in more sensitive areas.

Moreover, this is perhaps the recommendation that is more difficult to instrument in procurement terms (under the EU rules), as the consideration of ‘public benefit’ seems to be a matter for the contracting authority’s sole assessment, which could eventually lead to a cancellation—with or without retendering—of the procurement. It is difficult to see how to design evaluation tools (in terms of both technical specifications and award criteria) capable of capturing the insight that ‘public benefit extends beyond value for money and also includes considerations about transparency of the decision-making process and other factors that are included in these guidelines’. This should thus likely be built into the procurement process through opportunities for the contracting authority to discontinue the project (with no or limited compensation), which also points towards the structure of the innovation partnership as the regulated procedure most likely to fit.

3. Aim to include your procurement within a strategy for AI adoption across government and learn from others.

This is mainly aimed at ensuring cross-sharing of experiences and at concentrating the need for specific AI-based solutions, which makes sense. The difficulty will be in the practical implementation of this in a quickly-changing setting, which could be facilitated by the creation of a mandatory (not necessarily public) centralised register of AI-based projects, as well as the consideration of the creation and mandatory involvement of a specialised administrative unit. This would be linked to the general comment on the need to invest in skills, but could alleviate the financial impact by making the resources available across Government rather than having each contracting authority create its own expert team.

4. Ensure that legislation and codes of practice are incorporated in the RFP.

Both aspects of this guideline are problematic to a lawyer’s eyes. It is not a matter of legal imperialism to simply consider that there have to be more general mechanisms to ensure that procurement procedures (not only for digital technologies) are fully legally compliant.

The recommendation to carry out a comprehensive review of the legal system to identify all applicable rules and then ‘Incorporate those rules and norms into the RFP by referring to the originating laws and regulations’ does not make a lot of sense, since the inclusion or not in the RFP does not affect the enforceability of those rules, and given the practical impossibility for a contracting authority to assess the entirety of rules applicable to different tenderers, in particular if they are based in other jurisdictions. It would also create all sorts of problems in terms of potential claims of legitimate expectations by tenderers. Moreover, under EU law, there is case law (such as Pizzo and Connexxion Taxi Services) that creates conflicting incentives for the inclusion of specific references to rules and their interpretation in tender documents.

The recommendation on balancing trade secret protection and public interest, including data privacy compliance, is just insufficient and falls well short of the challenge of addressing these complex issues. The tension between general duties of administrative law and the opacity of algorithms (in particular where they are protected by IP or trade secrets protections) is one of the most heated ongoing debates in legal and governance scholarship. It also obviates the need to distinguish between the different rules applicable to the data and to the algorithms, as well as the paramount relevance of the General Data Protection Regulation in this context (at least where EU data is concerned).

5. Articulate the technical feasibility and governance considerations of obtaining relevant data.

This is, in my view, the strongest part of the guidelines. The stress on the need to ensure access to data as a pre-requisite for any AI project and the emphasis and detail put in the design of the relevant data governance structure ahead of the procurement could not be clearer. The difficulty, however, will be in getting most contracting authorities to this level of data-readiness. As mentioned above, the guidelines assume a level of competence that seems too advanced for most contracting authorities potentially interested in carrying out AI-based projects, or that could benefit from them.

6. Highlight the technical and ethical limitations of using the data to avoid issues such as bias.

This guideline is also premised on advanced knowledge and understanding of the data by the contracting authority, and thus creates the same challenges (as further discussed below).

7. Work with a diverse, multidisciplinary team.

Once again, this will be expensive and create some organisational challenges (as also discussed below).

8. Focus throughout the procurement process on mechanisms of accountability and transparency norms.

This is another rather naive and limited aspect of the guidelines, in particular the final point that ‘If an algorithm will be making decisions that affect people’s rights and public benefits, describe how the administrative process would preserve due process by enabling the contestability of automated decision-making in those circumstances.' This is another of the hotly-debated issues surrounding the deployment of AI in the public sector and it seems unlikely that a contracting authority will be able to provide the necessary answers to issues that are yet to be determined—eg the difficult interpretive issues surrounding solely automated processing of personal data under the General Data Protection Regulation, as discussed in eg M Finck, ‘Automated Decision-Making and Administrative Law’ (2019) Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition Research Paper No. 19-10.

9. Implement a process for the continued engagement of the AI provider with the acquiring entity for knowledge transfer and long-term risk assessment.

This is another area of general strength in the guidelines, which under EU procurement law should be channeled through stringent contract performance conditions (Art 70 Directive 2014/24/EU) or, perhaps even better, by creating secondary regulation on mandatory on-going support and knowledge transfer for all AI-based implementations in the public sector.

The only aspect of this guideline that is problematic concerns the mention that, in relation to ethical considerations, ‘Bidders should be able not only to describe their approach to the above, but also to provide examples of projects, complete with client references, where these considerations have been followed.’ This would clearly be a problem for new entrants, as well as generate rather significant first-mover advantages for undertakings with prior experience (likely in the private sector). In my view, this should be removed from the guidelines.

10. Create the conditions for a level and fair playing field among AI solution providers.

This section includes significant challenges concerning issues related to the ownership of IP on AI-based solutions. Most of the recommendations seem rather complicated to implement in practice, such as the reference to the need to ‘Consider strategies to avoid vendor lock-in, particularly in relation to black-box algorithms. These practices could involve the use of open standards, royalty-free licensing and public domain publication terms’, or to ‘'consider whether [the] department should own that IP and how it would control it [in particular in the context of evolution or new design of the algorithms]. The arrangements should be mutually beneficial and fair, and require royalty-free licensing when adopting a system that includes IP controlled by a vendor’. These are also extremely complex and debated issues and, once again, it seems unlikely that a contracting authority will be able to provide all relevant answers.

Overall assessment

The main strength of the guidelines lies in its recommendations concerning the evaluation of data availability and quality, as well as the need to create robust data governance frameworks and the need to have a deep insight into data limitations and biases (guidelines 5 and 6). There are also some useful, although rather self-explanatory reminders of basic planning issues concerning the need to ensure the relevant skillset and the unavoidable multidisciplinarity of teams working in AI (guidelines 3 and 7). Similarly, the guidelines provide some very high-level indications on how to structure the procurement process (guidelines 1, 2 and 9), which will however require much more detailed (future/additional) guidance before they can be implemented by a contracting authority.

However, in all other aspects, the guidelines work as an issue-spotting instrument rather than as a guidance tool. This is clearly the case concerning the tensions between data privacy, good administration and proprietary protection of the IP and trade secrets underlying AI-based solutions (guidelines 4, 8 and 10). In my view, rather than taking the naive—and potentially misleading—approach of indicating the issues that contracting authorities need to address (in the RFP, or elsewhere) as if they were currently (easily, or at all) addressable at that level of administrative practice, the guidelines should provide sufficiently precise and goal-oriented recommendations on how to do so if they are to be useful. This is not an easy task and much more work seems necessary before the document can provide useful support to contracting authorities seeking to implement procedures for the procurement of AI-based solutions. I thus wonder how much learning can the guidelines generate in the pilots to be conducted in the UK and elsewhere. For now, I would recommend other governments to wait and see before ‘adopting’ the guidelines or treating them as a useful policy tool, in particular if that discouraged them from carrying out their own efforts in developing actionable guidance on how to procure AI-based solutions.

Finally, it does not take much reading between the lines to realise that the challenges of developing an enabling data architecture and upskilling the public sector (not solely the procurement workforce, and perhaps through specialised units, as a first step) so that it is able to identify the potential for AI-based solutions and to adequately govern their design and implementation remain as very likely stumbling blocks in the road towards deployment of public sector AI. In that regard, general initiatives concerning the availability of quality procurement data and the necessary reform of public procurement teams to fill the data science and programming gaps that currently exist should remain the priority—at least in the EU, as discussed in A Sanchez-Graells, EU Public Procurement Policy and the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Pushing and Pulling as One? (2019) SSRN working paper, and in idem, 'Some public procurement challenges in supporting and delivering smart urban mobility: procurement data, discretion and expertise', in M Finck, M Lamping, V Moscon & H Richter (eds), Smart Urban Mobility – Law, Regulation, and Policy, MPI Studies on Intellectual Property and Competition Law (Berlin, Springer, 2020) forthcoming.