In their recent paper Government Purchasing to Improve Public Health: Theory Practice and Evidence, Noonan, Sell, Miller and Rubin explore how using government purchasing power to stimulate demand for healthier products provides a pathway to healthier food purchasing. At first sight, this is yet an additional instance of the use of public procurement to achieve secondary policies [see Prof. Arrowsmith's taxonomy of horizontal policies in procurement here] and, consequently, deserves some attention.

As the authors clearly stress,

The sheer amount of money government spends on procurement gives it a unique capacity to shape markets that, in turn, may affect public health. Through public procurement, government can, for example influence private companies competing for its business. Government’s influence can shape not only the types of products and services offered to government by private contractors, but markets themselves and the choices available to both corporate and individual consumers.

And, it is precisely this vast potential to shape (rectius, distort) the markets where the public buyer is active that justifies the need to take such impacts on commercial markets when designing public procurement rules and practice [as clearly emphasized recently by Prof. Yukins and Cora here, and as I have argued elsewhere]. However well-intended the 'secondary policy' promoted by the government, it may (will) come at a significant (and opaque) cost if it is not thoroughly assessed and carefully designed in view of its potential impact on the competitive dynamics of the markets concerned.

Focusing on the promotion of public health, Noonan, Sell, Miller and Rubin consider that

Although the specific elements and the aims of healthy procurement policies may vary, the key component of such initiatives is their use of government’s role as a buyer to shape the food environment in ways that promote better public health [...] Through healthy procurement, governments have an opportunity not only to improve the nutritional quality of the food they distribute or sell to the public, but by increasing the market demand for and availability of healthful products, to influence the options available to a much broader range of consumers.

Government procurement policies provide an alternative to policies where government regulates industry directly. Rather than establishing rules that require an industry to alter its products to meet certain standards, government can purchase products that already meet those standards. This approach can alleviate the administrative burden for the government; overcome political resistance often associated with traditional regulation; facilitate less adversarial relationships with private industry that places more emphasis on achieving outcomes than on punishing violations; and stimulate and promote innovation that the market, alone, may not produce (emphasis added).

The use of public procurement as a tool of industrial policy has been discussed for the best part of the last 25 years (see Geroski's seminal work in 1990). As a counter-argument to the advantages perceived by Noonan, Sell, Miller and Rubin, I think that it is clear that the use of public procurement as a regulatory tool creates significant issues of democratic and legitimacy deficit, as well as difficulties in monitoring and oversight--not to mention the potential (implicit) economic costs and losses in economic efficiency that would have otherwise been identified in the regulatory impact assessment (RIA) / cost-benefit analysis that would have preceded the adoption of the regulation now substituted with public procurement practice. Therefore, the picture is far from the ideal / neutral description provided by Noonan, Sell, Miller and Rubin.

Therefore, it should not be lightly used as the preferred 'regulatory tool' and, in any case, the implications of allowing the government to intervene in the market through the sheer use of its buying power would then need to be subjected to some kind of check and balance--which, in my view, should be competition / antitrust law and, more specifically, the rules on abuse of dominance / monopolisation [Sanchez Graells, Public Procurement and the EU Competition Rules (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2011) ch 4].

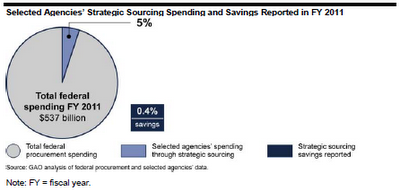

The process diagram designed by Noonan, Sell, Miller and Rubin is interesting because it helps explain the way in which secondary policies work and the (indirect?) way in which the substitution of legislation with procurement (specifications) may affect industry structure.

|

| Noonan, Sell, Miller and Rubin (2013: 8) circles added. |

It is clear that moving public health (or any other secondary policy) from the set of legal requirements to the public procurement specifications completely alters the framework in which the public buyer operates, sets it free from significant regulatory constraints, and diminishes the transparency and predictability of the system for companies active in these sectors. On the other hand, the expected industry adjustment may not always be comprehensive, and it can generate a truncation of an economic market (eg that for foodstuffs) into two artificial (sub)markets: a 'public market for food' and a 'private market for food'. The economic consequences of such truncation are hard to predict but, in all likelihood, they are bound to be negative from a social welfare standpoint.

However, in the specific case of 'healthy procurement' discussed by Noonan, Sell, Miller and Rubin, it seems apparent that the pursuit of public health objectives is done exclusively through the setting of the 'technical' specifications of the food to be provided (in most instances, to schools). In this regard, the promotion of public health in procurement should not be seen as a 'classical' exercise of secondary policy promotion, since the government is defining what to buy and the 'healthy' component is intrinsic to the goods to be delivered. In that regard, the choice of healthy food for schools seems unobjectionable also from a competition perspective. The issue would be different if the government decided to buy from vendors that only sold 'healthy food'--an issue that, at least in the European Union, has been clearly prohibited by the Court of Justice in the Commission v Netherlands (Fair Trade) case.

In any case, given the growing attention to the promotion of public health and the prevention of obesity and its related health issues (see the World Health Organisation and its initiatives), this new potential area of pursuit of 'secondary' / horizontal policies in public procurement deserves academic and policy-making attention.