With business sustainability in mind and in search of sustainable governmental behaviour, especially in terms of public purchasing practices, circularity seems like a fitting concept for fulfilling public needs in a sustainable manner (see eg Geissdoerfer et al: 2016). Given the hurdles with the implementation of green public procurement practices across the EU, and the struggles in furthering sustainable public procurement (going beyond environmental to also add social concerns), I expected that circular public procurement would be an exception and applicable only to a handful of cases. And indeed, it did not take much research to verify that the application of circularity across European public procurement is scarce at its best: while listed under green public procurement, circular public procurement exhibits few best practices across the EU that mostly arose at the local level (see eg this 2018 best practice report).

While it might be argued that circularity by definition requires local action, that does not prevent the development of practices at a regional, national or even supra-national level in specific sectors with potential to become circular, e.g. energy sector, construction sector and waste management. Yet, whether we speak about circularity in the framework of private markets or public procurement, it is absolutely indispensable to embed circular practices in the framework of sustainability and not simply formulate it under the framework of waste management.

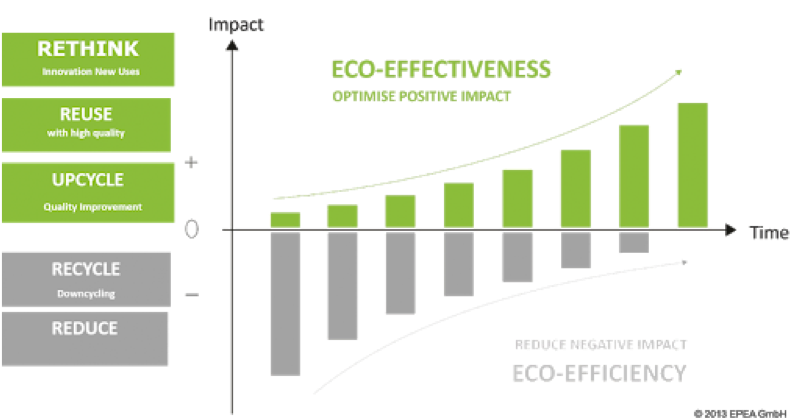

Much has been said on recycling, less on the cycle. Seeing circularity as an exercise of recycling and bringing materials back into the loop has been widespread, leading to even higher production and consumption and straying away from true sustainability. That being said, the underpinning reasons for such developments do not lie solely in private market practices, but also stem from the lack of knowledge on circularity and policy incoherence on the national and EU level in general.

What is (true) circularity?

Applying to both private and public markets, the notion of circularity should be clear. Recycling comes last. The whole purchasing procedure needs to be rethought and redesigned to accommodate more sustainable decisions and close the loop of linear practices as in ‘buy, use, dispose.’ Already at the stage of making the purchase decision, circularity demands us to rethink: do we need the product, service or works in question? Could we upcycle a product that we already own to fulfil that need? Could the need be filled by buying a service instead of the product or conversely leasing or renting the product? If the answer to those questions is no, then we need to purchase the product, service or work in question demanding a long life-time evaluation model.

Here the companies engaging in circular production need to provide a life-long guarantee, user manual, strategic design that facilitates reparability, minimal use of raw materials and energy (and its responsible sourcing, accounting for the social aspect of sustainability), use of renewable energy and efficient service and maintenance in case of a product fault. Spare part guarantee, service agreements, small repairs, standard components and easy disassembly are the must-haves under a truly sustainable circular economy.

Reuse and sometimes upcycling are the key. Recycling under a circular model is truly the last resort and its success in extracting useful materials for further production actually depends on the way the product was designed: the absence of hazardous materials, the possibility to disassemble the product into different materials with ease, the possibility of downcycling and upcycling of the materials. These notions all run counter to the current linear economy: and the implications of such systemic change on business models and private markets as we know them will be significant, causing significant policy spill over effects and demanding the elimination of existing policy incoherences inhibiting such a transition. This piece aims to provide further food for thought on the system as it is regarding private and public markets; discussing the current state of affairs, the impediments to a higher uptake of circular practices and the policy spill over effects of a successful implementation of circularity as a general exercise.

Where are we at? – the European Commission’s Action Plan

In terms of EU policy on circular economy in general, the European Commission has issued an ambitious circular economy package—which surprisingly focuses on waste management and bringing resources back in the loop—coupled with two subsequent implementation reports in 2017 and 2019. While the package recognises that the value of circular economy lies also in job creation, savings for businesses and the reduction of EU carbon emissions; the action plan on the matter focuses heavily on reforming the waste management legislation, albeit briefly reflecting also on the broader aspects of circular economy such as job creation, innovative design, business models, research, re-manufacturing, product development and food waste. The wrong signal is therefore sent to the private and public market: the focus on getting scarce materials back into the loop instead of a systemic change of production processes themselves. This influences private and public markets and reinforces the idea that the only issue with traditional linear production and consumption processes is the scarcity of (raw) materials.

Further reinforcing this idea, the EU study on Accelerating the transition to the circular economy focuses on public funds employed to that effect, omitting the fact that this represents only a fraction of the funds needed for a true systemic change. The study has been seen as an accelerator for the deployment of the circular economy, discussed in the framework of new circular business models and in the framework of waste management (id at 10). While the need for extensive financing has been repeatedly highlighted (eg in this 2017 report’s estimate of EUR 320 billion by 2025) for a systemic transition to circular economy (with estimated combined benefits of such shift of EUR 500 billion), the focus of the report has been on providing such finance in the current ‘business as usual’ framework, advocating for higher investment in such transition by the EU, without a comparative assessment of the current private financial market frameworks and its indispensable role in such transition (cfr this call for integrating externalities in the existing risk assessment frameworks).

Arguing for a systemic approach and a stronger focus on private finance offerings, especially with regards to small and medium-size enterprises (see here and here), points to the insufficiency of public funds for the transition to a more circular economy. To boost the private finance offerings, there is a need for a systemic change of financial systems to account for the inherent risks of the current linear business models, thereby eliminating persistent unfair competitive advantage for linear business models in the access-to-finance scenario. Not incorporating the change of linear risk assessment practices in greater detail into the EU action plan is a pitfall that needs to be remedied, qualifying change that needs to occur regarding the traditional access-to-funding setting in order to accommodate circular business and the changes it entails for ‘business-as-usual’ also in terms of the access-to-finance.

The structural flaw of underestimating the risks of linear projects and overestimating the risks of circular economy projects will not be remedied simply by taxonomy and EU funds: the financial systems on their own need to ‘circularise’ their finance offerings: the world as we know it, business as usual, is about to change and it could cost them more than just their reputation. Asset backed loans will need to change into ‘relationship’ backed loans, which presupposes also changes and ameliorations to contract laws to ensure monetised value to relationships as steering wheels of the new circular economy.

The lack of circularity in finance influences the offerings of the private market and the innovation necessary for circular solutions, which will in turn influence also the success of circular public procurement: the public funds and practices in innovation procurement cannot produce a sufficient amount of circular procurement to create a strong movement on the private market.

What are the impediments to a higher uptake of circular practices and what are their implications?

Aside from these two broader policy concerns, there are some specific impediments to circularity in public procurement: the first is the low uptake of green public procurement (GPP) across the EU,[1] impeding the insertion of circularity as the next step of GPP and the second the lack of regional, national and supranational best practices to that effect.

The integration between public procurement and circular economy itself is at its early stages at the EU level, where the incorporation of social, environmental and economic specifications into public procurement is not at a sufficiently high level to produce an indirect effect on products and consumers themselves and thereby stimulating circular economy. Furthermore, as majority of circular innovation stems from small and medium sized enterprises, it is crucial to further facilitate their access to public procurement systems, aside from general efforts to support the implementation of sustainable public procurement.

While the Eco-design Directive 2009/125/EC incentivises Member States to implement waste-preventing public procurement strategies according to information about the products’ technical durability, simultaneously suggesting the recycling requirements to be designed accounting for corresponding requirements for waste treatment in the waste legislation related to product, significantly supporting the circular flow of substances and materials, it is still strongly focused on waste management. Once again, here the notion of circularity supports more the linear production models than it does true circularity: while waste management and preservation of materials is important, determining the initial need for production and the potential for lease, reuse and upcycle is more important in terms of circularity.

The second supporting tool for circular public procurement, the Environmental Footprint Initiative of the European Commission, aims at providing a harmonisation process for the development of a scientific and consensus-based method, trying to inform and direct consumer choices with clear and comparable environmental information. Again, while reliable information is an indispensable steppingstone for determining sustainability hotspots, it is a truly preliminary and indirect step towards circular procurement. It does not provide for a true move from linearity to circularity.

Aside from the general concerns introduced above, the private sector further encounters impediments to circularity in current legislation on plastics recycling, competition law and the general corporate law favouring and prioritising linear business practices, lacking clear guidance on circularity. These are all examples of policy incoherence, some representing a direct example of incoherence (the silence of corporate legal frameworks on the social norm of shareholder primacy,[2] the plastic packaging requirements preventing the use of recycled plastics), others an indirect example (competition law).

Coupled with the abovementioned issues of financial law, these impediments are sufficient to significantly reduce the development of new circular solutions beyond pure recycling efforts. Additionally, the indirect policy incoherence in terms of competition policy as it stands, needs to be revised simultaneously to other sustainable changes to EU legal frameworks, and we have not accounted yet for those changes to a significant extent. If circularity is to be a tool towards achieving true sustainability, the traditional notions of ‘separating’ competitors and keeping them from cooperating will need to be revised. Circular systems have a need to be interconnected, cooperating and sharing, especially as reuse, repair and upcycling are the building blocks of circular economy. This calls for a systemic change of competition laws in themselves.

Furthermore, to aid the financing of this transition, traditional property and contract law will need to develop additional institutions to account for a different economy, one not based on assets as in material assets but rather relationships as assets. The road towards true circularity is still long, but these policy spill over considerations need to be resolved simultaneously with other sustainable changes to areas directly connected with sustainability in order to achieve a timely change towards truly sustainable circularity.

Where to now?

To conclude, a systemic change requires efforts of policymakers, private and public market actors as well as consumers. The above presented reflections represent just a fraction of what we will have to deal with in terms of transition towards sustainability and I would love to hear about any additional concerns and/or solutions to the policy issue that you have encountered in your professional field. I would gratefully any feedback or suggestions at lela.melon@upf.edu.

Lela Mélon is a lawyer and an economist, specialised in sustainable corporate law. Lela started her sustainability career in 2014 with her research on shareholder primacy in corporate law. She is currently charge of the Marie Curie Sklodowska funded project ‘Sustainable Company’ at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. She has co-authored and authored monographs, published several scientific articles in the field of sustainable corporate lawand sustainable public procurement and presented her work at conferences across Europe, as well as introduced sustainable corporate law curricula in several universities in Europe.

[1] Mélon, L. ‘More than a nudge? Arguments and tools for mandating green public procurement in the EU.’ Working Paper, Conference Corporate Sustainability Reforms Oslo 2019.

[2] Mélon, L. Shareholder Primacy and Global Business (Routledge 2018); Sjafjell, B. (2015) Shareholder Primacy: The Main Barrier to Sustainable Companies, University of Oslo Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2015-37.