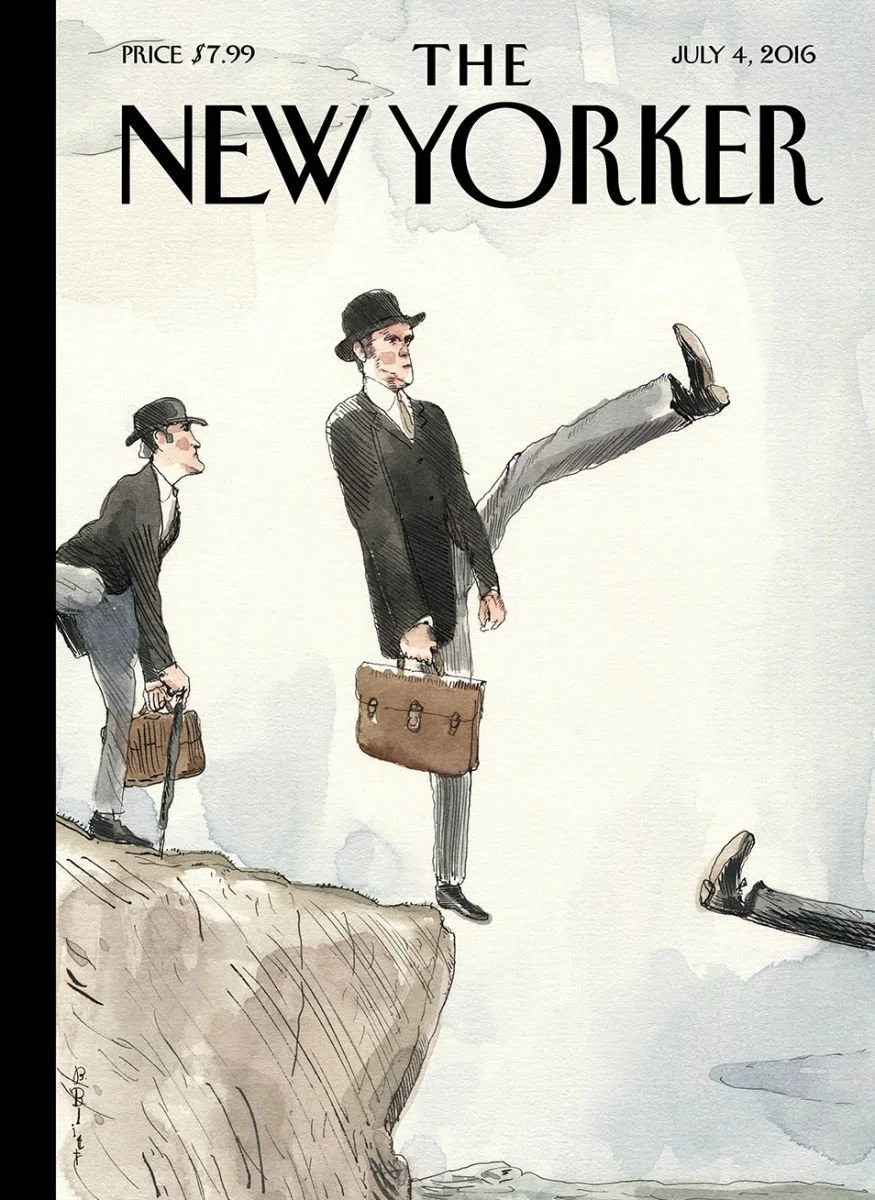

This new guest post by Dr Deividas Soloveičik provides interesting background on another reference for a preliminary ruling to the CJEU by the Supreme Court of Lithuania. On this occasion, the case raises interesting questions around the balance between procurement and competition law, but also about the regulatory and self-organisation space left to Member States in the context of the EU regulation of in-house provision arrangements. It will be interesting to keep an eye on the case, as it brings an opportunity for the CJEU to expand its case law after its recast in eg Art 12 of Directive 2014/24/EU.

NOTHING LEFT TO SAY ABOUT THE IN-HOUSE EXEMPTION? THINK TWICE

On April 13, 2018 the Supreme Court of Lithuania (SCoL) decided to stay proceedings and refer a question for preliminary ruling to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in a case that raises new questions related to the in-house exemption (civil case No. e3K-3-120-469/2018). This time, the SCoL wishes to find out if Member States are allowed to limit or even ban the use of the in-house exemption, as is the case in Lithuania. Besides, the SCoL seeks clarification on the balance to be struck between public procurement and competition law. In particular, the SCoL wishes to know whether the in-house exemption may be applicable where the same supply of goods or services can be delivered by the market. In other words, whether the contracting authority can buy in-house when there is available supply in the market. These are challenging issues and the CJEU’s views will be much awaited. Before providing an overview of the facts of the case, it is worth noting the Lithuanian legal background, which influenced the decision of the SCoL to refer the case to the CJEU, as well as the whole legal problem.

Lithuanian legal background

The in-house exemption has been regulated in the public procurement law of Lithuania since 2010. The criteria for its use were those set by the CJEU in Teckal and the subsequent case-law on the subject. Since then, in-house contracts became very common in particular at local level. Many contracting authorities and entities used them with their controlled companies, and in many cases the exemption became the general rule. However, this practice became both a legal problem and a national political scandal when it was noticed that the in-house exception was implemented in order to support a modus operandi whereby contracting authorities used the in-house exemption to award contracts to their subsidiaries, so that the latter did not have to hold themselves as contracting authorities and could thus buy services and supplies from the market like private operators. This created a situation where contracting authorities circumvented the public procurement rules just by using an intermediary (their subsidiaries) that triggered the in-house exemption. This practice even generated the Litspecmet case (C-567/15, EU:C:2017:736), already decided by the CJEU (see a comment here).

As a result of these abuses, the implementation of the 2014 EU Public procurement directives led Lithuania to practically ban the in-house mechanism. The new Lithuanian procurement law states that any governmental authority and / or private companies directly controlled or owned by the State shall have no right to enter into in-house agreements of whatsoever nature. Other contracting authorities, such as municipalities and their controlled companies, have the privilege of the in-house exemption. However, this only applies in cases when there is either (i) no supply from the market, or (ii) there are no possibilities to buy good quality in a way that guarantees the quality, availability or continuity of the services and (iii) if the awardee is a contracting authority itself. Moreover, the Competition Council became very active in tracing each contracting authority that uses the in-house exception and seeking the judicial repeal of such agreements on the basis of the Law on competition, which inter alia states that neither the State, governmental or other official authorities may have any privilege against any other market player (ie sets out a principle of competitive neutrality). Therefore, in fact, on the few occasions where in-house agreements are not forbidden by the Lithuanian Law on public procurement, they will most likely be challenged by the Competition Council on the basis of the Lithuanian Law on competition. Thus, in practice the possibility for the award of public contracts in-house is either excluded or very risky.

The Irgita case

In the case the SCoL has now referred to the CJEU, a Municipality concluded a public contract for the upkeep of green areas with economic operator Irgita. It was specified in the contract that the volume of services was a maximum and that the contracting authority was not obliged to buy all the services. The Municipality was to solely pay for the services actually provided according to the rates specified in the contract. Thus, the final price payable to the service provider depended on the volume of services rendered by the latter. In case the services required by the contracting authority exceeded the maximum amount specified in the contract, a separate procurement would be arranged.

Later on, the contracting authority approached the Public Procurement Office in order to get approval to conclude an in-house contract regarding the same services with another economic operator that (i) is a contracting authority itself, (ii) is controlled by the contracting authority (Municipality) and (iii) receives 90 percent of its income from the contracting authority (Municipality). Such approval was granted, and the contracting authority concluded the in-house contract with its controlled economic operator.

After the in-house contract was concluded, Irgita filed a claim by which it argued that the decision of the Municipality was unlawful, on the basis of the following arguments: (i) the contracting authority was not in a position to enter into the in-house contract because, at the time of its conclusion, the public contract with the claimant was still in force; (ii) the disputed decision and the in-house contract did not meet the requirements set in the Law on public procurement and the Law on competition of Lithuania, as it distorts free and fair competition between economic operators because the contracting authority’s contractual partner is being granted privileges while the other (private) economic operators are being discriminated against.

The court of first instance did not establish a breach of competition, while the Court of Appeals considered that the in-house contract was unlawful, in particular because it reduced the volume of services available for provision by Irgita in the first place. In deciding to refer the case to the CJEU, the SCoL started its reasoning by the stating that this was the first time it had an opportunity to examine the balance between public procurement and competition law in the context of in-house arrangements. The SCoL found that it was very likely that the concept of in-house agreement in the realm of public procurement law was a category of EU law and thus not open to separate interpretation under national legislation. If that was the case, then it would be very dubious that Member States were entitled to limit the right of the contracting authority to engage in this kind of transactions.

The SCoL held that:

- The CJEU has substantiated the in-house doctrine as an exemption from compliance with otherwise applicable public procurement requirements;

- The CJEU has repeatedly held that since the concept of a public contract does not refer to the national legal regulation of the Member States, the notion and the whole concept of in-house agreement must be regarded as falling exclusively within the scope of EU law and must be interpreted without regard to national law (Jean Auroux Case, C-220/05). In this matter, the SCoL stated that CJEU case-law implies a possibility of treating the in-house exemption as an independent legal norm of EU law;

- From the case-law of the CJEU, it is clear that the in-house exemption does not infringe the rights of private economic operators, they are not discriminatory, because the economic operators controlled by the contracting authorities do not enjoy any privileges (Sea, C-573/07; Carbotermo ir Consorzio Alisei, C-340/04; Undis Servizi, C-553/15). In other words, the SCoL emphasized that if it is deemed that the in-house agreements are legitimate, then it hardly can be that they limit and distort the competition in all cases. Otherwise, they would not be allowed pursuant to the long-standing jurisprudence of the CJEU.

On the basis of the above-mentioned considerations, the SCoL considered that there is a need to address the following questions to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling:

1. In circumstances such as those in the present case, where the procedure for the conclusion of the in-house contract was initiated under Directive 2004/18, but the contract itself was concluded on 19 May 2016, does the in-house contract fall within the scope of Directive 2014/18 or Directive 2014/24 in case of an invalidity?

2. Assuming that the disputed in-house contract falls within the scope of Directive 2004/18:

(a) must Article 1(2)(a) of this Directive (but not limited to this provision), in accordance with the judgments of the CJEU in Teckal (C-107/98), Jean Auroux and Others (C-220/05) and ANAV (C-410/04) etc be understood and interpreted in such a way that the concept of in-house falls within the scope of EU law and the content and application of that concept is not affected by the national law of the Member States, inter alia, restrictions on the conclusion of such contracts, such as the condition that public service contracts cannot guarantee the quality, availability or continuity of the services provided?

(b) If the answer to the preceding question is negative, i.e. the concept of in-house in part or in full falls within the scope of the national law of the Member States, is the abovementioned provision of the Directive 2004/18 to be interpreted as meaning that the Member States have the discretion to impose restrictions or additional conditions for the establishment of the in-house contract (in comparison with EU law and the interpretation of the CJEU case-law), but it can be implemented only by specific and clear rules of the substantive law on public procurement ?

3. Assuming that the disputed in-house contract falls within the scope of Directive 2014/24:

(a) must Article 1(4), Article 12 and Article 36 of the Directive, jointly or severally (but not limited to), in accordance with the judgments of the CJEU in Teckal (C-107/98), Jean Auroux and Others (C-220/05) and ANAV (C-410/04) etc be understood and interpreted in such way that the concept of in-house falls within the scope of EU law and that the content and application of this concept are not affected by the national law of the Member States, inter alia, restrictions on the conclusion of such contracts, such as the condition that public service contracts cannot guarantee quality, availability or continuity of the services provided?

(b) If the answer to the preceding question is negative, i.e. the concept of in-house is partly or fully covered by the national law of the Member States, must the provisions of Article 12 of Directive 2014/24 be interpreted in such way that the Member States have the discretion to impose restrictions or additional conditions for the establishment of in-house contracts (in comparison with EU law and the interpretation of the CJEU case-law), but it can be implemented only by specific and clear rules of the substantive law on public procurement?

4. Irrespective of which of the directives covers the in-house contracts, must the principles of equality, non-discrimination and transparency (Article 2 of the Directive 2004/18, Article 18 of Directive 2014/24), the general prohibition of discrimination on grounds of nationality (Article 18 TFEU), freedom of establishment (Article 49 TFEU) and freedom to provide services (Article 56 TFEU), the possibility of granting exclusive rights to undertakings (Article 106 TFEU), and the case-law of the CJEU (Teckal, ANAV, Sea, Undis Servizi etc) be understood and interpreted as meaning that an in-house contract concluded by a contracting authority and another distinct legal entity which is controlled by the contracting authority in a manner similar to its own departments and where part of such legal entity’s activities is in the interest of the contracting authority, is per se lawful, and that it does not infringe the rights of the other economic operators to fair competition, to not being discriminated against and for no privileges to be provided to the controlled legal entity that has concluded the in-house contract?

The enquiry made by the SCoL shows that it basically wishes to clarify a few very interesting and important legal points, which will influence the development of the in-house exception. Firstly, the SCoL tries to understand whether the in-house exemption is an autonomous concept of EU law or not. Because if it really is, then naturally there will be less discretion left to the Member States in terms of in-house procurement regulation. In other words, Member States would not be allowed to limit the in-house agreement possibility and only the case-law would be the source of the in-house legality in each particular case. Secondly, the SCoL tries to understand, at least indirectly, what are the dynamics between competition law and the law on public procurement.

The situation where, on the one hand, public procurement law allows for in-house arrangements but, on the other hand, the Competition Council and its application of the rules of the Law on competition will be waiting around the corner, is not acceptable. The SCoL correctly noted that such situations jeopardise the legitimate expectations of economic operators and contracting authorities and make the whole legal ecosystem related to this issue very blurry. Without a doubt, the now much anticipated answers from the CJEU will have a strong impact on the application of the in-house exception. In Lithuania it might even mean, in case of positive answers given by the CJEU to most of the questions, that half of Art. 10 of the Law on public procurement, which regulates the “remainders” of in-house exemption, will be inapplicable due to the supremacy of the EU law and will have to be amended by the legislator.

Dr. Deividas Soloveičik, LL.M

Dr Deividas Soloveičik is a Partner and Head of Public Procurement practice at COBALT Lithuania. He represents clients before national courts at all instances and arbitral institutions in civil and administrative cases, provides legal advice to Lithuanian and foreign private clients and contracting authorities, including the European Commission , on the legal aspects of public procurement and pre-commercial procurement.

Dr Soloveičik is an Associate Professor and researcher in commercial law at Vilnius University and a contributor to legal publications. He also closely cooperates with globally recognized academic members of the legal profession. Since 2011, MCIArb. Dr Soloveičik is a member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators; since 2016, he is a member of the European Assistance for Innovation Procurement – EAFIP initiative promoted by the European Commission and a recommended arbitrator at Vilnius Court of Commercial Arbitration.

* Guest blogging at HTCAN: If you would like to contribute a blog post for How to Crack a Nut, please feel free to get in touch at a.sanchez-graells@bristol.ac.uk. Your proposals and contributions will be most warmly welcomed!