Exclusion grounds are now established in reg.57 of the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 (PCR2015), which follows closely Article 57 of Directive 2014/24. The rules establish three groups of exclusion grounds: mandatory, hybrid and discretionary; as well as some minimum and maximum requirements concerning the timing of the exclusion and its duration. The main novelty concerns the regulation of self-cleaning mechanisms aimed at restoring reliability of economic operators affected by exclusion grounds.

The following comments are based on my paper "Exclusion, Qualitative Selection and Short-listing", in F Lichère, R Caranta & S Treumer (eds), Modernising Public Procurement. The New Directive, vol. 6 European Procurement Law Series (Copenhagen, DJØF, 2014) 97-129, where further references are provided. All references are to the provisions in Dir 2014/24, but they apply mutatis mutandis to reg.57 PCR2015. I know that the comments are long, but I hope they will be useful. Pedro has complemented them with some views and references, particularly on self-cleaning.

(1) Extension of the grounds for mandatory exclusion of economic operators: an emphasis on the fight against fraud and corruption

Art 57 of Dir 2014/24 alters and extends the grounds for mandatory exclusion currently foreseen in Article 45 of Directive 2004/18. According to Art 57(1) of Dir 2014/24, the current four grounds for mandatory exclusion of economic operators convicted by final judgment are maintained, which include the following offences: i) participation in a criminal organisation, ii) corruption, iii) fraud, and iv) money laundering. The references to the statutory instruments where these offences are regulated have been updated, but the regime remains substantially identical. However, Art 57(1) and 57(2) of Dir 2014/24 significantly extend the remit of the grounds for mandatory disqualification.

Reg.57(1)(n) PCR2015 tries to cover this expansion of grounds by including a catch-all final renvoi provision that comprises any offence within the meaning of Art 57(1) of Dir 2014/24 as defined by the law of any jurisdiction outside England and Wales and Northern Ireland; or created, after the day on which these Regulations were made, in the law of England and Wales or Northern Ireland. Hence, t

he

enforcement of this provision will not be without difficulty, given the

variety of criminal laws that might need checking, but it seems in line

with the requirements of Article IV:4(c) of the revised version of the

2011 WTO Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA), which mandates that contracting authorities conduct ‘covered procurement in a transparent and impartial manner that: (c) prevents corrupt practices’ and which makes explicit reference to the United Nations Convention against Corruption.

Therefore, the scope of this ground for mandatory exclusion seems to

have been significantly broadened (at least potentially, and depending

on the actions of the Member States to adopt aggressive anti-corruption

legislation) (see also below). Such broadening can even result in a

certain extraterritoriality in the application of this ground for

exclusion when national criminal laws concerned with corruption cover

instances of bribery of third country officials following the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery. For general discussion, see the contributions to G M Racca and C R Yukins (eds), Integrity and Efficiency in Sustainable Public Contracts (Brussels, Bruylant, 2014).

Some of the novelties in Dir 2014/24 and the PCR2015 are worth highlighting. Firstly, in connection with corruption, the ground is extended beyond the ‘EU definition’ of this offence and will now cover ‘corruption as defined in the national law of the contracting authority or the economic operator’ [art 57(1)(b) dir 2014/24]. According to regs.57(1)(b) to (d) PCR2015, this covers corruption within the meaning of section 1(2) of the Public Bodies Corrupt Practices Act 1889 or section 1 of the Prevention of Corruption Act 1906, the common law offence of bribery, as well as bribery within the meaning of sections 1, 2 or 6 of the Bribery Act 2010, or section 113 of the Representation of the People Act 1983.

Secondly, in relation to terrorism, two new mandatory grounds for exclusion are created for terrorist financing [art 57(1)(e) dir 2014/24] and for terrorist offences or offences linked to terrorist activities [art 57(1)(d) dir 2014/24]. According to regs.57(1)(f) and (g), this covers any offence listed in section 41 of the Counter Terrorism Act 2008, or in Schedule 2 to that Act where the court has determined that there is a terrorist connection; as well as any offence under sections 44 to 46 of the Serious Crime Act 2007 which relates to an offence coverered by the Counter Terrorism Act 2008.

Thirdly, a new ground for mandatory exclusion is created to tackle child labour and other forms of trafficking in human beings,

as defined in the corresponding EU instruments [art 57(1)(f) dir

2014/24]. Regs.57(1) (j) to (m) PCR2015 extend that to any offence under

section 4 of the Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants, etc.)

Act 2004, under section 59A of the Sexual Offences Act 2003, section 71

of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, or any offence in connection with

the proceeds of drug trafficking within the meaning of section 49, 50

or 51 of the Drug Trafficking Act 1994.

Fourthly, lack of payment of taxes or social security contributions becomes a ground for mandatory disqualification where

this has been established by a judicial or administrative decision

having final and binding effect in accordance with the legal provisions

of the country in which it is established or with those of any of the

jurisdictions of the United Kingdom [art 57(2) dir 2014/24 and

reg.57(3) PCR2015]. This makes mandatory the grounds for discretionary

exclusion previously foreseen in Arts 45(2)(e) and 45(2)(f) of Dir

2004/18 where there is a final and binding jurisdictional or

administrative decision—and, otherwise, it will remain a discretionary

ground for exclusion under Art 57(2)II of Dir 2014/24 / reg.57(4)

PCR2015 (see below).

Lastly, Art 57(1) in fine of Dir 2014/24 [reg.57(2) PCR2015] clarifies the provisions in Art 45(1) in fine

of Dir 2004/18 and extends the obligation to exclude the economic

operator on the basis of any of the prior grounds for exclusion ‘where

the person convicted by final judgment is a member of the

administrative, management or supervisory body of that economic operator

or has powers of representation, decision or control therein’. The

only exception to this rule concerns the lack of payment of taxes and

social security contributions, but this seems open to contention. In my

opinion, at least where lack of payment is related to the activities of

the economic operator, the rule should apply despite the legal person

not being the one directly convicted or the direct addressee of the

jurisdictional or administrative decision confirming the breach of tax

or social security rules.

It is also worth stressing that, similar to what was already provided for in Art 45(1)III of Dir 2004/18, Art 57(3) of Dir 2014/24 [reg.57(6) PCR2015] foresees that ‘Member States may provide for a derogation from the mandatory exclusion … on an exceptional basis, for overriding reasons relating to the public interest such as public health or protection of the environment’. In this regard, I would submit that the interpretation of the concept of ‘general interest’ developed by the CJEU in the area of free movement (of goods, in relation to art 36 TFEU and the so called Cassis rule of reason) may be of relevance for the interpretation and construction of such potential derogations.

It is also worth stressing that, similar to what was already provided for in Art 45(1)III of Dir 2004/18, Art 57(3) of Dir 2014/24 [reg.57(6) PCR2015] foresees that ‘Member States may provide for a derogation from the mandatory exclusion … on an exceptional basis, for overriding reasons relating to the public interest such as public health or protection of the environment’. In this regard, I would submit that the interpretation of the concept of ‘general interest’ developed by the CJEU in the area of free movement (of goods, in relation to art 36 TFEU and the so called Cassis rule of reason) may be of relevance for the interpretation and construction of such potential derogations.

Moreover, in the case of the lack of payment of taxes and social security contributions, Art 57(3) in fine of Dir 2014/24 [reg.57(7) PCR2015] authorises Member States to create an (additional) derogation ‘where an exclusion would be clearly disproportionate, in particular where only minor amounts of taxes or social security contributions are unpaid or where the economic operator was informed of the exact amount due following its breach of its obligations relating to the payment of taxes or social security contributions at such time that it did not have the possibility of taking measures [addressed at sorting out the situation …] before expiration of the deadline for requesting participation or, in open procedures, the deadline for submitting its tender’.

In order to ensure consistency of such a de minimis exception to the mandatory rule established in Art 57(2) of Dir 2014/24, a common definition of what constitutes ‘minor amounts’ seems necessary. Otherwise, this is an issue likely to end up being referred to the CJEU for a preliminary interpretation, which answer may be almost impossible for the Court to provide, unless it is clearly willing to create a judicial de minimis threshold for this ground of exclusion [which it is extremely unlikely, particularly in view of the formalistic approach followed in the recent decision in Consorzio Stabile Libor Lavori Pubblici, C-358/12, EU:C:2014:2063]

.

(2) Extension of the discretionary grounds for exclusion of economic operators

Following the distinction in Art 45(2) of Dir 2004/18, which established additional exclusion grounds that contracting authorities can decide to apply at their discretion, Arts 57(2)II and 57(4) of Dir 2014/24 extend the current list of discretionary grounds for the exclusion of economic operators that contracting authorities may decide to use (or may be required by their Member State to use) to exclude any economic operator from participation in a procurement procedure.

With

some drafting modifications, but with fundamentally the same content,

the list provided in Arts 57(2)II and 57(4) covers the current grounds

of exclusion on the basis of: i) bankruptcy, judicial administration or

assimilated situations, including being part of ongoing proceedings, ii)

demonstrated grave professional misconduct, which renders its integrity

questionable, iii) lack of payment of taxes or social security

contributions not established by a jurisdictional or administrative

decision having final and binding effect (otherwise, the exclusion

ground becomes mandatory, above), and iv) serious misrepresentation in

supplying the information required for the verification of the absence

of grounds for exclusion or the fulfillment of the selection criteria,

or withholding of such information. Furthermore, and similarly to what

happened with mandatory exclusion grounds, Art 57(4) of Dir 2014/24

extends and broadens the list of situations in which an economic

operator can (or must) be excluded. This is covered by regs.57(4) and

(8) PCR2015. Some provisions deserve additional comments.

Firstly, given the creation of new rules on the European Single Procurement Document

(ie the submission of self-declarations) rather than the supply of full

evidence supporting the inexistence of grounds for exclusion and

compliance with qualitative selection criteria (art 59 dir 2014/24), the

ground concerned with misrepresentation and withholding of information

is extended to cover situations where the economic operator is ‘not able to submit the supporting documents required pursuant to Article 59’ [art 57(4)(h) dir 2014/24]. This establishes a iuris et de iure presumption that the economic operator that cannot supply the required supporting documentation has gravely misrepresented its suitability and qualification

to be awarded the contract and seems a natural extension of this

grounds for exclusion—which, in my opinion, should however be a

mandatory ground for exclusion.

Secondly,

contracting authorities can exclude economic operators where they can

demonstrate by any appropriate means violations of applicable

obligations established by Union law or national law compatible with it

in the field of social and labour law or environmental law or of the

international social and environmental law provisions listed in Annex X

[arts 18(2) and 57(4)(a) dir 2014/24]. Other than the considerations

related to the use of public procurement as a lever to reinforce

compliance with such ‘secondary policies’, this new ground for exclusion

raises the issue of the standard of diligence that the contracting

authority must discharge in order not to be negligently unaware of the

existence of such violations. Given that there are different

standards for different exclusion grounds, these are issues that are

prone to litigation and that will likely require interpretation by the

CJEU. In my view, any means of proof should suffice to proceed to such

exclusion, but the violation should be of a sufficient entity as to

justify the exclusion under a proportionality test (similarly to what

the new Directive proposes in terms of lack of payment of taxes or

social security contributions, or ‘grave’ professional misconduct),

since exclusion for any minor infringement of social, labour or

environmental requirements may be disproportionate and, ultimately, not

in the public interest if it affects the level and intensity of

competition for the contracts.

Thirdly, the Directive creates a new (limited) ground for the exclusion of infringers of competition law. Indeed, contracting authorities can now exclude economic operators where they have ‘sufficiently

plausible indications to conclude that the economic operator has

entered into agreements with other economic operators aimed at

distorting competition’ [art 57(4)(d)]. This should be read in connection with the OECD’s July 2012 Recommendation on Fighting Bid Rigging in Public Procurement

and with the many actions undertaken by national competition

authorities of some of the Member States to better liaise with

contracting authorities and entities, and to advocate for competition

law compliance in the public procurement setting.

In my opinion, this

new ground for exclusion is excessively limited and, given the gravity

of bid rigging, it should be a ground for the mandatory exclusion of the

offenders [see A Sanchez Graells, ‘Prevention and Deterrence of Bid Rigging: A Look from the New EU Directive on Public Procurement’, in G M Racca and C R Yukins (eds), Integrity and Efficiency in Sustainable Public Contracts (Brussels, Bruylant, 2014) 137-157]. As

a matter of diligence (and subject to applicable domestic rules), in

these cases, the contracting authority seems likely to be under a duty

to report this behaviour to the national competition authority and to

cooperate as much as necessary with the ensuing competition law

investigation.

Fourthly, the Directive creates yet another ground for exclusion based on poor past performance by the economic operator. Under this new ground, contracting authorities can exclude economic operators that have ‘shown

significant or persistent deficiencies in the performance of a

substantive requirement under a prior public contract, a prior contract

with a contracting entity or a prior concession contract which led to

early termination of that prior contract, damages or other comparable

sanctions’ [art 57(4)(g)]. The introduction of past performance as

an exclusion ground responds to the requests made for a long time by

practitioners and brings the EU system closer to that of the US.

Remarkably, this provision may overturn the practice and case law that

prevented contracting authorities to take past performance into

consideration. In my opinion, even if good past performance should not

be taken into consideration either for selection or award purposes

(because of the effect it has in entrenching the incumbents), it seems

sensible to introduce its use for ‘negative’ purposes in order to allow

contracting authorities to (self)protect their interests by not engaging

contractors prone not to deliver as expected. This seems particularly

proportionate in view of the rules on ‘self-cleaning’ that allow

contractors to compensate such poor past performance by showing that

they have implemented changes to avoid them recurring.

Interestingly, a (soft) corruption-related new ground for exclusion is also created.

Further to the ground for mandatory exclusion of economic operators

engaged in (hard) corruption (above), contracting authorities can

exclude economic operators where they have ‘undertaken to unduly

influence the decision-making process of the contracting authority, to

obtain confidential information that may confer upon it undue advantages

in the procurement procedure or to negligently provide misleading

information that may have a material influence on decisions concerning

exclusion, selection or award’ [art 57(4)(i) Dir 2014/24]. To be

sure, some or all of these activities may be caught by the definition of

corruption under domestic laws and, consequently, could substantively

overlap with the mandatory ground for exclusion in Art 57(1)(b) of Dir

2014/24 (above). However, the mandatory ground for exclusion is only

triggered if the economic operator has already been convicted by final

judgment. Consequently, the virtuality of Art 57(4)(i) of Dir 2014/24

resides in allowing the contracting authority to immediately exclude any

economic operator engaged in (quasi)corruption or that has otherwise

tried to tamper with the integrity of the tender procedure. As a matter

of diligence (and subject to applicable domestic rules), in these cases,

the contracting authority seems likely to be under a duty to report

this behaviour to the competent authorities or courts and to push for

criminal prosecution.

Finally, and strengthening the general

remarks contained in the recitals of previous generations of procurement

directives, the new Directive has also created two complementary

grounds for the exclusion of tenderers in cases of conflict of interest,

either generally [arts 24 and 57(4)(e)], or as a result of the prior

involvement of candidates or tenderers in the preparation of the

procedure [arts 41 and 57(4)(f)]. Indeed, the contracting authority can

exclude economic operators ‘where a conflict of interest within the

meaning of Article 24 cannot be effectively remedied by other less

intrusive measures’ , or ‘where a distortion of competition from the

prior involvement of the economic operators in the preparation of the

procurement procedure, as referred to in Article 41, cannot be remedied

by other, less intrusive measures’. These provisions should allow

contracting authorities to ensure the integrity of the procurement

process, despite the fact that the conflict of interest will also affect

themselves (or members of their staff) and, consequently, these may end

up being provisions which disappointed tenderers use in order to

challenge their lack of application, rather than provisions directly and

positively applied by the contracting authorities themselves—depending,

of course, on the institutional robustness of the specific contracting

authority concerned (and the litigation environment in any given Member

State).

(3) Exclusion possible at any point of the tender procedure

(3) Exclusion possible at any point of the tender procedure

Art

57(5) of Dir 2014/24 [regs. 57(9) and (10) PCR2015] introduces a much

needed clarification on the possibility or duty for contracting

authorities to exclude economic operators at any moment during the

procedure. This clarifies that exclusion grounds (both those that are

mandatory as a matter of EU law, and those that Member States make

mandatory in their jurisdictions) should be considered unwaivable [ie

mandatory because they represent the ‘public interest’, unless some of

them are configured in a discretionary manner by domestic law, as

allowed for by art 57(4) dir 2014/24] and that contracting authorities

should be aware of them and check for compliance throughout the tender

procedure. Equally, contracting authorities are now given express legal

support for the exclusion of tenderers at late stages of the tender

procedure, therefore nullifying any claims based on the potential

(legitimate?) expectations derived from not having been excluded at the

beginning of the procedure. According to Article 57(5) of Dir 2014/24,

it is now clear that a contracting authority would not be going against

its own prior acts and thus not be estopped from excluding tenderers

previously admitted to (or not excluded from) the tender procedure.

More specifically, Art 57(5) of Dir 2014/24 establishes that contracting authorities ‘shall

at any time during the procedure exclude an economic operator where it

turns out that the economic operator is, in view of acts committed or

omitted either before or during the procedure,’ convicted by final

judgment of one of the qualified crimes of Art 57(1), or where the

contracting authority is aware that the economic operator is in breach

of its obligations relating to the payment of taxes or social security

contributions and where this has been established by a judicial or

administrative decision having final and binding effect [Art 57(2) dir

2014/24; reg.57(9) PCR2015]. Moreover, ‘contracting authorities may

exclude or may be required by Member States to exclude an economic

operator where it turns out that the economic operator is, in view of

acts committed or omitted either before or during the procedure, in one

of the situations referred to in paragraph 4’ [see also reg.57(10)

PCR2015]. This new provision is due to generate significant legal

effects and may be open to litigation to test its boundaries against the

general principles of equal treatment, protection of legitimate

expectations and legal certainty—which can raise ‘constitutional’ law

issues in some of the domestic jurisdictions.

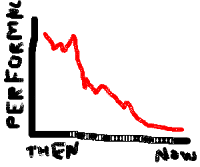

(4) Harmonisation of minimum rules on maximum exclusion periods Following the position in Arts 45(1) and 45(2) of Dir 2004/18, Art 57(7) of Dir 2014/24 requires that Member States specify the implementing conditions for the exclusion of economic operators by law, regulation or administrative provision and always having regard for EU law. However, it establishes new minimum rules concerning maximum exclusion periods. Indeed, Member States shall ‘determine the maximum period of exclusion if no [self-cleaning] measures … are taken by the economic operator to demonstrate its reliability. Where the period of exclusion has not been set by final judgment, that period shall not exceed five years from the date of the conviction by final judgment in the cases referred to in paragraph 1 and three years from the date of the relevant event in the cases referred to in paragraph 4’ of that same Art 57 of Dir 2014/24.

This has been transposed in regs.57(11) and (12) PCR2015, whereby in the cases referred to in paragraphs (1) to (3), the period during which the economic operator shall (subject to paragraphs (6), (7) and (14)) be excluded is 5 years from the date of the conviction; whereas in the cases referred to in paragraphs (4) and (8), the period during which the economic operator may (subject to paragraph (14)) be excluded is 3 years from the date of the relevant event.

Under

the EU regime, in the specific case of (mandatory or discretionary)

exclusion due to lack of payment of taxes or social security

contributions, the exclusion seems to be subject to an indefinite period

that will only finish once the economic operator settles the

outstanding debt or enters into arrangements to do so. This derives from

Art 57(2) in fine Dir 2014/24 which determines that these grounds for exclusion ‘shall

no longer apply when the economic operator has fulfilled its

obligations by paying or entering into a binding arrangement with a view

to paying the taxes or social security contributions due, including,

where applicable, any interest accrued or fines’ [this is also

established in reg.57(5) PCR2015]. Reg.57(11) PCR2015 has opted to apply

the maximum of 5 years of exclusion to economic operators in breach of

their obligations to pay taxes or social security contributions as

established by a judicial or administrative decision having final and

binding effect [reg.57(3)]. In my view, this can be a deviation from

the standard interpretation of Art 57 Dir 2014/24. However, given that

it sets a limit to a situation that would otherwise be potentially

indefinite, I find it hard that this will trigger litigation or, indeed,

a finding of infringement against the UK due to improper transposition.

More generally and in my opinion, such different treatment for specific exclusion grounds under EU law (ie the possibility to indefinitely exclude operators in breach of tax or social security obligations) seems

unwarranted and other exclusion grounds that indicate the existence of

similarly ongoing infringements (such as those concerned with

infringements of social, labour and environmental law, or those

concerning bankruptcy and administration) should also be subjected to

indefinite exclusion until the economic operator complies with the

relevant legislation. This result may be achieved anyway depending on

the domestic rules applicable to continued infringements, but some

further clarification and harmonisation could be desirable in order to

keep the level playing field. Moreover, rules on the recognition of

domestic exclusion decisions in the rest of the Member States could also

be necessary, although this can be indirectly achieved by the European

Single Procurement Document.

(5) Self-cleaning and corporate compliance programs

As a novelty, and in order to allow ‘for the possibility that economic operators can adopt compliance measures aimed at remedying the consequences of any criminal offences or misconduct and at effectively preventing further occurrences of the misbehaviour’ [rec (102) dir 2014/24], Art 57(6) of Dir 2014/24 [regs.57(13) to (17) PCR2015] establishes rules on self-cleaning and promotes the adoption of corporate compliance programs. Under the rules of Art 57(6) Dir 2014/24, any economic operator that should be excluded under any of the grounds in 57(1) or 57(4) can provide evidence to the effect that measures it has taken are sufficient to demonstrate its reliability despite the existence of a relevant ground for exclusion and, if such evidence is considered as sufficient by the contracting authority, the economic operator concerned shall not be excluded.

The Directive includes a list of compensatory measures that, as a minimum, shall include proof that the economic operator ‘has paid or undertaken to pay compensation in respect of any damage caused by the criminal offence or misconduct, clarified the facts and circumstances in a comprehensive manner by actively collaborating with the investigating authorities and taken concrete technical, organisational and personnel measures that are appropriate to prevent further criminal offences or misconduct’ [reg.57(15) PCR2015]. Furthermore, the discretion retained by the contracting authority to assess the sufficiency of the self-cleaning measures adopted by the economic operator is modulated by the requirement that they ‘shall be evaluated taking into account the gravity and particular circumstances of the criminal offence or misconduct’ [reg.57(16) PCR2015]. As a specific requirement of the duty of good administration and the obligation to provide reasons for any decision adopted in a procurement procedure, ‘[w]here the measures are considered to be insufficient, the economic operator shall receive a statement of the reasons for that decision’ [see reg.57(17) PCR2015]—which, in my opinion, shall be amenable to judicial review under the applicable rules of each Member State.

Oddly, the Directive restricts the possibility of implementing self-cleaning measures for economic operators that have ‘been excluded by final judgment from participating in procurement procedures [which] shall not be entitled to make use of [this] possibility … during the period of exclusion resulting from that judgment in the Member States where the judgment is effective’. This shows a lack of trust in self-cleaning measures and imposes exclusion as an irreversible sanction in the Member State adopting that decision (but, oddly, not in other Member States), which can sometimes disproportionately reduce competition (as well as creating a dual standard applicable in ‘domestic’ and ‘cross-border’ participation in procurement by that operator). Therefore, in my opinion, self-cleaning should also be available in these cases, which may justify a particularly tough approach to the evaluation of the sufficiency of the measures implemented by the economic operator. At least, an escape clause should exist in these cases to waive, substitute or defer the exclusion on grounds of public interest if having the economic operator excluded actually harms the interests of the contracting authority (which may be the case in highly concentrated or specialised markets).

However, even if the exclusion in Art 57(6) in fine of Dir 2014/24 is criticisable, it clearly imposes that '[a]n economic operator which has been excluded by final judgment from

participating in procurement or concession award procedures shall not be

entitled to make use of the possibility provided for under this

paragraph during the period of exclusion resulting from that judgment in

the Member States where the judgment is effective'. This provision certainly has direct effect. Consequently, contracting authorities must apply it, regardless of the fact that reg.57 PCR2015 does not include such a rule. Otherwise, in my view, can lead to an investigation by the European Commission for improper transposition of the rules in Art 57 Dir 2014/24 against the UK.