On 30 October 2023, G7 leaders published the Hiroshima Process International Guiding Principles for Advanced AI system (the G7 AI Principles), a non-exhaustive list of guiding principles formulated as a living document that builds on the OECD AI Principles to take account of recent developments in advanced AI systems. The G7 stresses that these principles should apply to all AI actors, when and as applicable to cover the design, development, deployment and use of advanced AI systems.

The G7 AI Principles are supported by a voluntary Code of Conduct for Advanced AI Systems (the G7 AI Code of Conduct), which is meant to provide guidance to help seize the benefits and address the risks and challenges brought by these technologies.

The G7 AI Principles and Code of Conduct came just two days before the start of the UK’s AI Safety Summit 2023. Given that the UK is part of the G7 and has endorsed the G7 Hiroshima Process and its outcomes, the interaction between the G7’s documents, the UK Government’s March 2023 ‘pro-innovation’ approach to AI and its aspirations for the AI Safety Summit deserves some comment.

G7 AI Principles and Code of Conduct

The G7 AI Principles aim ‘to promote safe, secure, and trustworthy AI worldwide and will provide guidance for organizations developing and using the most advanced AI systems, including the most advanced foundation models and generative AI systems.’ The principles are meant to be cross-cutting, as they target ‘among others, entities from academia, civil society, the private sector, and the public sector.’ Importantly, also, the G7 AI Principles are meant to be a stop gap solution, as G7 leaders ‘call on organizations in consultation with other relevant stakeholders to follow these [principles], in line with a risk-based approach, while governments develop more enduring and/or detailed governance and regulatory approaches.’

The principles include the reminder that ‘[w]hile harnessing the opportunities of innovation, organizations should respect the rule of law, human rights, due process, diversity, fairness and non-discrimination, democracy, and human-centricity, in the design, development and deployment of advanced AI system’, as well as a reminder that organizations developing and deploying AI should not undermine democratic values, harm individuals or communities, ‘facilitate terrorism, enable criminal misuse, or pose substantial risks to safety, security, and human rights’. State (AI users) are reminder of their ‘obligations under international human rights law to promote that human rights are fully respected and protected’ and private sector actors are called to align their activities ‘with international frameworks such as the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises’.

These are all very high level declarations and aspirations that do not go much beyond pre-existing commitments and (soft) law norms, if at all.

The G7 AI Principles comprises a non-exhaustive list of 11 high-level regulatory goals that organizations should abide by ‘commensurate to the risks’—ie following the already mentioned risk-based approach—which introduces a first element of uncertainty because the document does not establish any methodology or explanation on how risks should be assessed and tiered (one of the primary, and debated, features of the proposed EU AI Act). The principles are the following, prefaced by my own labelling between square brackets:

[risk identification, evaluation and mitigation] Take appropriate measures throughout the development of advanced AI systems, including prior to and throughout their deployment and placement on the market, to identify, evaluate, and mitigate risks across the AI lifecycle;

[misuse monitoring] Patterns of misuse, after deployment including placement on the market;

[transparency and accountability] Publicly report advanced AI systems’ capabilities, limitations and domains of appropriate and inappropriate use, to support ensuring sufficient transparency, thereby contributing to increase accountability.

[incident intelligence exchange] Work towards responsible information sharing and reporting of incidents among organizations developing advanced AI systems including with industry, governments, civil society, and academia.

[risk management governance] Develop, implement and disclose AI governance and risk management policies, grounded in a risk-based approach – including privacy policies, and mitigation measures, in particular for organizations developing advanced AI systems.

[(cyber) security] Invest in and implement robust security controls, including physical security, cybersecurity and insider threat safeguards across the AI lifecycle.

[content authentication and watermarking] Develop and deploy reliable content authentication and provenance mechanisms, where technically feasible, such as watermarking or other techniques to enable users to identify AI-generated content.

[risk mitigation priority] Prioritize research to mitigate societal, safety and security risks and prioritize investment in effective mitigation measures.

[grand challenges priority] Prioritize the development of advanced AI systems to address the world’s greatest challenges, notably but not limited to the climate crisis, global health and education.

[technical standardisation] Advance the development of and, where appropriate, adoption of international technical standards.

[personal data and IP safeguards] Implement appropriate data input measures and protections for personal data and intellectual property.

Each of the principles is accompanied by additional guidance or precision, where possible, and this is further developed in the G7 Code of Conduct.

In my view, the list is a bit of a mixed bag.

There are some very general aspirations or steers that can hardly be considered principles of AI regulation, for example principle 9 setting a grand challenges priority and, possibly, principle 8 setting a risk mitigation priority beyond the ‘requirements’ of principle 1 on risk identification, evaluation and mitigation—which thus seems to boil down to the more specific steer in the G7 Code of Conduct for (private) organisations to ‘share research and best practices on risk mitigation’.

Quite how these principles could be complied by current major AI developers seems rather difficult to foresee, especially in relation to principle 9. Most developers of generative AI or other AI applications linked to eg social media platforms will have a hard time demonstrating their engagement with this principle, unless we accept a general justification of ‘general purpose application’ or ‘dual use application’—which to me seems quite unpalatable. What is the purpose of this principle if eg it pushes organisations away from engaging with the rest of the G7 AI Principles? Or if organisations are allowed to gloss over it in any (future) disclosures linked to an eventual mechanism of commitment, chartering, or labelling associated with the principles? It seems like the sort of purely political aspiration that may have been better left aside.

Some other principles seem to push at an open door, such as principle 10 on the development of international technical standards. Again, the only meaningful detail seems to be in the G7 Code of Conduct, which specifies that ‘In particular, organizations also are encouraged to work to develop interoperable international technical standards and frameworks to help users distinguish content generated by AI from non-AI generated content.’ However, this is closely linked to principle 7 on content authentication and watermarking, so it is not clear how much that adds. Moreover, this comes to further embed the role of industry-led technical standards as a foundational element of AI regulation, with all the potential problems that arise from it (for some discussion from the perspective of regulatory tunnelling, see here and here).

Yet other principles present as relatively soft requirements or ‘noble’ commitments issues that are, in reality, legal requirements already binding on entities and States and that, in my view, should have been placed as hard obligations and a renewed commitment from G7 States to enforce them. These include principle 11 on personal data and IP safeguards, where the G7 Code of Conduct includes as an apparent after thought that ‘Organizations should also comply with applicable legal frameworks’. In my view, this should be starting point.

This reduces the list of AI Principles ‘proper’. But, even then, they can be further grouped and synthesised, in my view. For example, principles 1 and 5 are both about risk management, with the (outward-looking) governance layer of principle 5 seeking to give transparency to the (inward-looking) governance layer in principle 1. Principle 2 seems to simply seek to extend the need to engage with risk-based management post-market placement, which is also closely connected to the (inward-looking) governance layer in principle 1. All of them focus on the (undefined) risk-based approach to development and deployment of AI underpinning the G7’s AI Principles and Code of Conduct.

Some aspects of the incident intelligence exchange also relate to principle 1, while some other aspects relate to (cyber) security issues encapsulated in principle 6. However, given that this principle may be a placeholder for the development of some specific mechanisms of collaboration—either based on cyber security collaboration or other approaches, such as the much touted aviation industry’s—it may be treated separately.

Perhaps, then, the ‘core’ AI Principles arising from the G7 document could be trimmed down to:

Life-cycle risk-based management and governance, inclusive of principles 1, 2, and 5.

Transparency and accountability, principle 3.

Incident intelligence exchange, principle 4.

(Cyber) security, principle 6.

Content authentication and watermarking, principle 7 (though perhaps narrowly targeted to generative AI).

Most of the value in the G7 AI Principles and Code of Conduct thus arises from the pointers for collaboration, the more detailed self-regulatory measures, and the more specific potential commitments included in the latter. For example, in relation to the potential AI risks that are identified as potential targets for the risk assessments expected of AI developers (under guidance related to principle 1), or the desirable content of AI-related disclosures (under guidance related to principle 3).

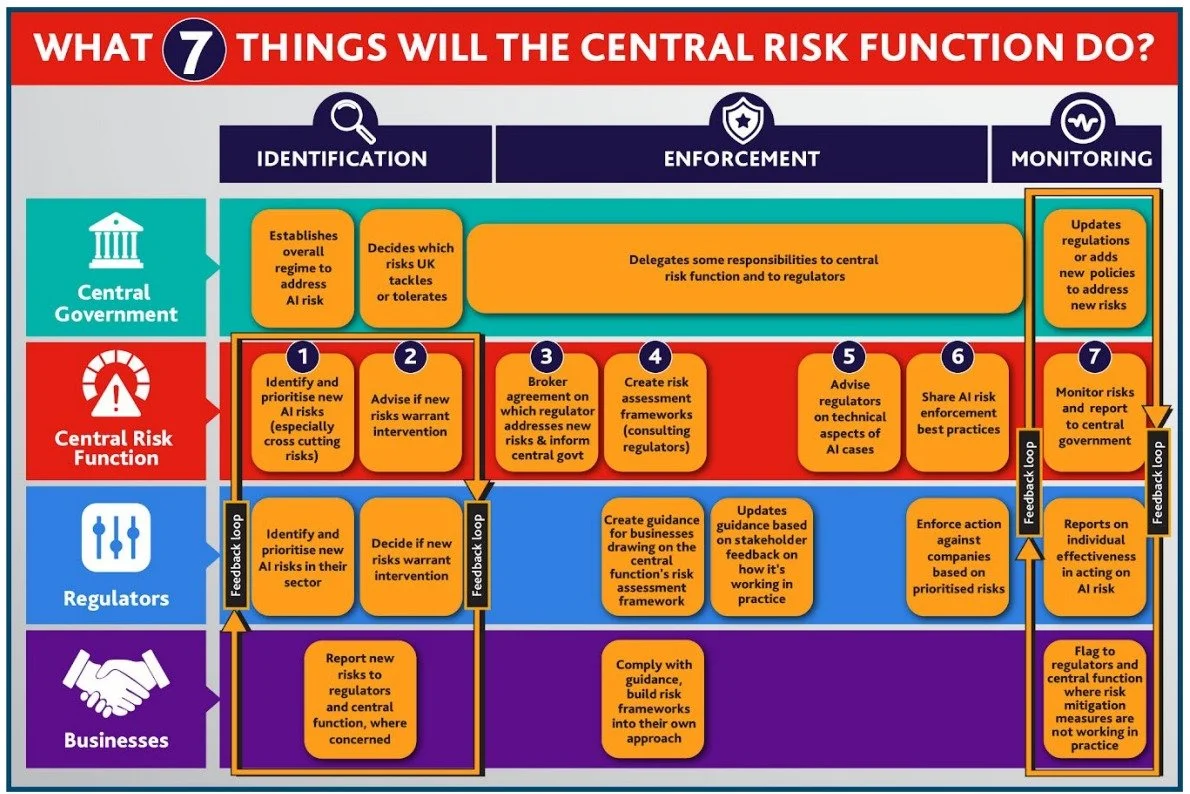

It is however unclear how these principles will evolve when adopted at the national level, and to what extent they offer a sufficient blueprint to ensure international coherence in the development of the ‘more enduring and/or detailed governance and regulatory approaches’ envisaged by G7 leaders. It seems for example striking that both the EU and the UK have supported these principles, given that they have relatively opposing approaches to AI regulation—with the EU seeking to finalise the legislative negotiations on the first ‘golden standard’ of AI regulation and the UK taking an entirely deregulatory approach. Perhaps this is in itself an indication that, even at the level of detail achieved in the G7 AI Code of Conduct, the regulatory leeway is quite broad and still necessitates significant further concretisation for it to be meaningful in operational terms—as evidenced eg by the US President’s ‘Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence’, which calls for that concretisation and provides a good example of the many areas for detailed work required to translate high level principles into actionable requirements (even if it leaves enforcement still undefined).

How do the G7 Principles compare to the UK’s ‘pro-innovation’ ones?

In March 2023, the UK Government published its white paper ‘A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation’ (the ‘UK AI White Paper’; for a critique, see here). The UK AI White Paper indicated (at para 10) that its ‘framework is underpinned by five principles to guide and inform the responsible development and use of AI in all sectors of the economy:

Safety, security and robustness

Appropriate transparency and explainability

Fairness

Accountability and governance

Contestability and redress’.

A comparison of the UK and the G7 principles can show a few things.

First, that there are some areas where there seems to be a clear correlation—in particular concerning (cyber) security as a self-standing challenge requiring a direct regulatory focus.

Second, that it is hard to decide at which level to place incommensurable aspects of AI regulation. Notably, the G7 principles do not directly refer to fairness—while the UK does. However, the G7 Principles do spend some time in the preamble addressing the issue of fairness and unacceptable AI use (though in a woolly manner). Whether placing this type of ‘requirement’ at a level or other makes a difference (at all) is highly debatable.

Third, that there are different ways of ‘packaging’ principles or (soft) obligations. Just like some of the G7 principles are closely connected or fold into each other (as above), so do the UK’s principles in relation to the G7’s. For example, the G7 packaged together transparency and accountability (principle 3), while the UK had them separated. While the UK explicitly mentioned the issue of AI explainability, this remains implicit in the G7 principles (also in principle 3).

Finally, in line with the considerations above, that distinct regulatory approaches only emerge or become clear once the ‘principles’ become specific (so they arguably stop being principles). For example, it seems clear that the G7 Principles aspire to higher levels of incident intelligence governance and to a specific target of generative AI watermarking than the UK’s. However, whether the G7 or the UK principles are equally or more demanding on any other dimension of AI regulation is close to impossible to establish. In my view, this further supports the need for a much more detailed AI regulatory framework—else, technical standards will entirely occupy that regulatory space.

What do the G7 AI Principles tell us about the UK’s AI Safety Summit?

The Hiroshima Process that has led to the adoption of the G7 AI Principles and Code of Conduct emerged from the Ministerial Declaration of The G7 Digital and Tech Ministers’ Meeting of 30 April 2023, which explicitly stated that:

‘Given that generative AI technologies are increasingly prominent across countries and sectors, we recognise the need to take stock in the near term of the opportunities and challenges of these technologies and to continue promoting safety and trust as these technologies develop. We plan to convene future G7 discussions on generative AI which could include topics such as governance, how to safeguard intellectual property rights including copyright, promote transparency, address disinformation, including foreign information manipulation, and how to responsibly utilise these technologies’ (at para 47).

The UK Government’s ambitions for the AI Safety Summit largely focus on those same issues, albeit within the very narrow confines of ‘frontier AI’, which it has defined as ‘highly capable general-purpose AI models that can perform a wide variety of tasks and match or exceed the capabilities present in today’s most advanced models‘. While the UK Government has published specific reports to focus discussion on (1) Capabilities and risks from frontier AI and (2) Emerging Processes for Frontier AI Safety, it is unclear how the level of detail of such narrow approach could translate into broader international commitments.

The G7 AI Principles already claim to tackle ‘the most advanced AI systems, including the most advanced foundation models and generative AI systems (henceforth "advanced AI systems")’ within their scope. It seems unclear that such approach would be based on a lack of knowledge or understanding of the detail the UK has condensed in those reports. It rather seems that the G7 was not ready to move quickly to a level of detail beyond that included in the G7 AI Code of Conduct. Whether significant further developments can be expected beyond the G7 AI Principles and Code of Conduct just two days after they were published seems hard to fathom.

Moreover, although the UK Government is downplaying the fact that eg Chinese participation in the AI Safety Summit is unclear and potentially rather marginal, it seems that, at best, the UK AI Safety Summit will be an opportunity for a continued conversation between G7 countries and a few others. It is also unclear whether significant progress will be made in a forum that seems rather clearly tilted towards industry voice and influence.

Let’s wait and see what the outcomes are, but I am not optimistic for significant progress other than, worryingly, a risk of further displacement of regulatory decision-making towards industry and industry-led (future) standards.