The UK’s Cabinet Office has published procurement policy note 2/24 on ‘Improving Transparency of AI use in Procurement’ (the ‘AI PPN’) because ‘AI systems, tools and products are part of a rapidly growing and evolving market, and as such, there may be increased risks associated with their adoption … [and therefore] it is essential to take steps to identify and manage associated risks and opportunities, as part of the Government’s commercial activities’.

The crucial risk the AI PPN seems to be concerned with relates to generative AI ‘hallucinations’, as it includes background information highlighting that:

‘Content created with the support of Large Language Models (LLMs) may include inaccurate or misleading statements; where statements, facts or references appear plausible, but are in fact false. LLMs are trained to predict a “statistically plausible” string of text, however statistical plausibility does not necessarily mean that the statements are factually accurate. As LLMs do not have a contextual understanding of the question they are being asked, or the answer they are proposing, they are unable to identify or correct any errors they make in their response. Care must be taken both in the use of LLMs, and in assessing returns that have used LLMs, in the form of additional due diligence.’

The PPN has the main advantage of trying to tackle the challenge of generative AI in procurement head on. It can help raise awareness in case someone was not yet talking about this and, more seriously, it includes an Annex A that brings together the several different bits of guidance issued by the UK government to date. However, the AI PPN does not elaborate on any of that guidance and is thus as limited as the Guidelines for AI procurement (see here), relatively complicated in that it points to rather different types of guidance ranging from ethics, to legal, to practical considerations, and requires significant knowledge and expertise to be operationalised (see here). Perhaps the best evidence of the complexity of the mushrooming sets of guidance is that the PPN itself includes in Annex A a reference to the January 2024 Guidance to civil servants on use of generative AI, which has been superseded by the Generative AI Framework for HMG, to which it also refers in Annex A. In other words, the AI PPN is not a ‘plug-and-play’ document setting out how to go about dealing with AI hallucinations and other risks in procurement. And given the pace of change in this area, it is also bound to be a PPN that requires multiple revisions and adaptations going forward.

A screenshot showing that the January guidance on generative AI use has been superseded (taken on 26 March 2024 10:20am).

More generally, the AI PPN is bound to be controversial and has already spurred insightful discussion on LinkedIn. I would recommend the posts by Kieran McGaughey and Ian Makgill. I offer some additional thoughts here and look forward to continuing the conversation.

In my view, one of the potential issues arising from the AI PPN is that it aims to cover quite a few different aspects of AI in procurement, as well as neglecting others. Slightly simplifying, there are three broad areas of AI-procurement interaction. First, there is the issue of buying AI-based solutions or services. Second, there is the issue of tenderers using (generative) AI to write or design their tenders. Third, there is the issue of the use of AI by contracting authorities, eg in relation to qualitative selection/exclusion, or evaluation/award decisions. The AI PPN covers aspects of . However, it is not clear to me that these can be treated together, as they pose significantly different policy issues. I will try to disentangle them here.

Buying and using AI

Although it mainly cross-refers to the Guidelines for AI procurement, the AI PPN includes some content relevant to the procurement and use of AI when it stresses that ‘Commercial teams should take note of existing guidance when purchasing AI services, however they should also be aware that AI and Machine Learning is becoming increasingly prevalent in the delivery of “non-AI” services. Where AI is likely to be used in the delivery of a service, commercial teams may wish to require suppliers to declare this, and provide further details. This will enable commercial teams to consider any additional due diligence or contractual amendments to manage the impact of AI as part of the service delivery.’ This is an adequate and potentially helpful warning. However, as discussed below, the PPN suggests a way to go about it that is in my view wrong and potentially very problematic.

AI-generated tenders

The AI PPN is however mostly concerned with the use of AI for tender generation. It recognises that there ‘are potential benefits to suppliers using AI to develop their bids, enabling them to bid for a greater number of public contracts. It is important to note that suppliers’ use of AI is not prohibited during the commercial process but steps should be taken to understand the risks associated with the use of AI tools in this context, as would be the case if a bid writer has been used by the bidder.’ It indicates some potential steps contracting authorities can take, such as:

‘Asking suppliers to disclose their use of AI in the creation of their tender.’

‘Undertaking appropriate and proportionate due diligence:

If suppliers use AI tools to create tender responses, additional due diligence may be required to ensure suppliers have the appropriate capacity and capability to fulfil the requirements of the contract. Such due diligence should be proportionate to any additional specific risk posed by the use of AI, and could include site visits, clarification questions or supplier presentations.

Additional due diligence should help to establish the accuracy, robustness and credibility of suppliers’ tenders through the use of clarifications or requesting additional supporting documentation in the same way contracting authorities would approach any uncertainty or ambiguity in tenders.’

‘Potentially allowing more time in the procurement to allow for due diligence and an increase in volumes of responses.’

‘Closer alignment with internal customers and delivery teams to bring greater expertise on the implications and benefits of AI, relative to the subject matter of the contract.’

In my view, there are a few problematic aspects here. While the AI PPN seems to try not to single out the use of generative AI as potentially problematic by equating it to the possible use of (human) bid writers, this is unconvincing. First, because there is (to my knowledge) no guidance whatsoever on an assessment of whether bid writers have been used, and because the AI PPN itself does not require disclosure of the engagement of bid writers (o puts any thought on the fact that third-party bid writers ma have used AI without this being known to the hiring tenderer, which would then require an extension of the disclosure of AI use further down the tender generation chain). Second, because the approach taken in the AI PP seems to point at potential problems with the use of (external, third-party) bid writers, whereas it does not seem to object to the use of (in-house) bid writers, potentially by much larger economic operators, which seems to presumptively not generate issues. Third, and most importantly, because it shows that perhaps not enough has been done so far to tackle the potential deceit or provision of misleading information in tenders if contracting authorities must now start thinking about how to get expert-based analysis of tenders, or develop fact-checking mechanisms to ensure bids are truthful. You would have thought that regardless of the origin of a tender, contracting authorities should be able to check their content to an adequate level of due diligence already.

In any case, the biggest issue with the AI PPN is how it suggests contracting authorities should deal with this issue, as discussed below.

AI-based assessments

The AI PPN also suggests that contracting authorities should be ‘Planning for a general increase in activity as suppliers may use AI to streamline or automate their processes and improve their bid writing capability and capacity leading to an increase in clarification questions and tender responses.’ One of the possibilities could be for contracting authorities to ‘fight fire with fire’ and also deploy generative AI (eg to make summaries, to scan for errors, etc). Interestingly, though, the AI PPN does not directly refer to the potential use of (generative) AI by contracting authorities.

While it includes a reference in Annex A to the Generative AI framework for HM Government, that document does not specifically address the use of generative AI to manage procurement processes (and what it says about buying generative AI is redundant given the other guidance in the Annex). In my view, the generative AI framework pushes strongly against the use of AI in procurement when it identifies a series of use cases to avoid (page 18) that include contexts where high-accuracy and high-explainability are required. If this is the government’s (justified) view, then the AI PPN has been a missed opportunity to say this more clearly and directly.

The broader issue of confidential, classified or proprietary information

Both in relation to the procurement and use of AI, and the use of AI for tender generation, the AI PPN stresses that it may be necessary:

‘Putting in place proportionate controls to ensure bidders do not use confidential contracting authority information, or information not already in the public domain as training data for AI systems e.g. using confidential Government tender documents to train AI or Large Language Models to create future tender responses.‘; and that

‘In certain procurements where there are national security concerns in relation to use of AI by suppliers, there may be additional considerations and risk mitigations that are required. In such instances, commercial teams should engage with their Information Assurance and Security colleagues, before launching the procurement, to ensure proportionate risk mitigations are implemented.’

These are issues that can easily exceed the technical capabilities of most contracting authorities. It is very hard to know what data has been used to train a model and economic operators using ‘off-the-shelf’ generative AI solutions will hardly be in a position to assess themselves, or provide any meaningful information, to contracting authorities. While there can be contractual constraints on the use of information and data generated under a given contract, it is much more challenging to assess whether information and data has been inappropriately used at a different link of increasingly complex digital supply chains. And, in any case, this is not only an issue for future contracts. Data and information generated under contracts already in place may not be subject to adequate data governance frameworks. It would seem that a more muscular approach to auditing data governance issues may be required, and that this should not be devolved to the procurement function.

How to deal with it? — or where the PPN goes wrong

The biggest weakness in the AI PPN is in how it suggests contracting authorities should deal with the issue of generative AI. In my view, it gets it wrong in two different ways. First, by asking for too much non-scored information where contracting authorities are unlikely to be able to act on it without breaching procurement and good administration principles. Second, by asking for too little non-scored information that contracting authorities are under a duty to score.

Too much information

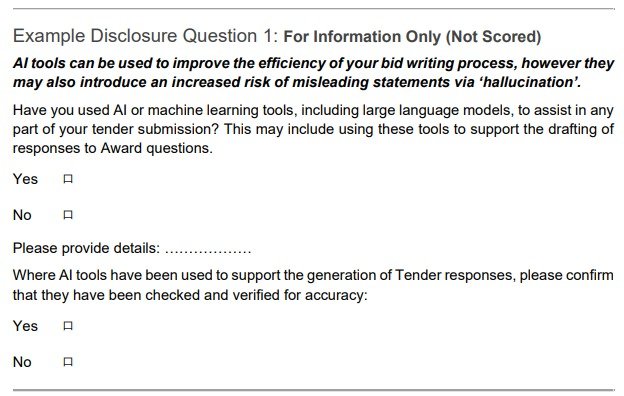

The AI PPN includes two potential (alternative) disclosure questions in relation to the use of generative AI in tender writing (see below Q1 and Q2).

I think these questions miss the mark and expose contracting authorities to risks of challenge on grounds of a potential breach of the principle of equal treatment and the duty of good administration. The potential breach of the duty of good administration could be on grounds that the contracting authority is taking irrelevant information into account in the assessment of the relevant tender. The potential breach of equal treatment could come if tenders with some AI-generated elements were subjected to significantly more scrutiny than tenders where no AI was used. Contracting authorities should subject all tenders to the same level of due diligence and scrutiny because, at the bottom of it, there is no reason to ‘take a tenderer at its word’ when no AI is used. That is the entire logic of the exclusion, qualitative selection and evaluation processes.

Crucially, though, what the questions seem to really seek to ascertain is that the tenderer has checked for and confirms the accuracy of the content of the tender and thus makes the content its own and takes responsibility for it. This could be checked generally by asking all tenderers to confirm that the content of their tenders is correct and a true reflection of their capabilities and intended contractual delivery, reminding them that contracting authorities have tools to sanction economic operators that have ‘negligently provided misleading information that may have a material influence on decisions concerning exclusion, selection or award’ (reg.57(8)(i)(ii) PCR2015 and sch.7 13(2)(b) PA2023). And then enforcing them!

Checking the ‘authenticity’ of tenders when in fact contracting authorities are meant to check their truthfulness, accuracy and deliverability would be a false substitution of the relevant duties. It would also potentially eschew the incentives to disclose use of AI generation (lest contracting authorities find a reliable way of identifying it themselves and start applying the exclusion grounds above)—as thoroughly discussed in the LinkedIn posts referred to above.

too little information

Conversely, the PPN takes too soft and potentially confusing an approach to the use of AI to deliver the contract. The proposed disclosure question (Q3) is very problematic. It presents as ‘for information only’ a request for information on the use of AI or machine learning in the context of the actual delivery of the contract. This is information that will either relate to the technical specifications, award criteria or performance clauses (or all of them) and there is no meaningful way in which AI could be used to deliver the contract without this having an impact on the assessment and evaluation of the tender. The question is potentially misleading not only because of the indication that the information would not be scored, but also because it suggests that the use of AI in the delivery of a service or product is within the discretion of the tenderers. In my view, this would only be possible if the technical specifications were rather loosely written in performance terms, which would then require a very thorough description and assessment of how that performance is to be achieved. Moreover, the use of AI would probably require a set of organisational arrangements that should also not go unnoticed or unchecked in the procurement process. Moreover, one of the main challenges may not be in the use of AI in new contracts (were tenderers are likely to highlight it to stress the advantages, or to justify that their tenders are not abnormally low in comparison with delivery through ‘manual’ solutions), but in relation to pre-existing contracts. It also seems that a broader policy, recommendation and audit of the use of generative AI for the delivery of existing contracts and its treatment as a (permissible??) contract modification would have been needed.

Final thought

The AI PPN is an interesting development and will help crystallise many discussions that were somehow hovering in the background. However, a significant rethink is needed and, in my view, much more detailed guidance is needed in relation to the different dimensions of the interaction between AI and procurement. There are important questions that remain unaddressed and, in my view, one of the most pressing ones concerns the balance between general regulation and the use of procurement to regulate AI use. While the UK government remains committed to its ‘pro-innovation’ approach and no general regulation of AI use is put in place, in particular in relation to public sector AI use, procurement will continue to struggle and fail to act as a regulator of the technology.