I look forward to delivering the lecture ‘Responsibly Buying Artificial Intelligence: A Regulatory Hallucination?’ as part of the Current Legal Problems Lecture Series 2023-24 organised by UCL Laws. The lecture will be this Thursday 23 November 2023 at 6pm GMT and you can still register to participate (either online or in person). These are the slides I will be using, in case you want to take a sneak peek. I will post a draft version of the paper after the lecture. Comments welcome!

What's the rush -- some thoughts on the UK's Foundation Model Taskforce and regulation by Twitter

I have been closely following developments on AI regulation in the UK, as part of the background research for the joint submission to the public consultation closing on Wednesday (see here and here). Perhaps surprisingly, the biggest developments do not concern the regulation of AI under the devolved model described in the ‘pro-innovation’ white paper, but its displacement outside existing regulatory regimes—both in terms of funding, and practical power.

Most of the activity and investments are not channelled towards existing resource-strained regulators to support them in their task of issuing guidance on how to deal with AI risks and harms—which stems from the white paper—but in digital industrial policy and R&D projects, including a new major research centre on responsible and trustworthy AI and a Foundation Model Taskforce. A first observation is that this type of investments can be worthwhile, but not at the expense of adequately resourcing regulators facing the tall order of AI regulation.

The UK’s Primer Minister is clearly making a move to use ‘world-leadership in AI safety’ as a major plank of his re-election bid in the coming Fall. I am not only sceptical about this move and its international reception, but also increasingly concerned about a tendency to ‘regulate by Twitter’ and to bullish approaches to regulatory and legal compliance that could well result in squandering a good part of the £100m set aside for the Taskforce.

In this blog, I offer some preliminary thoughts. Comments welcome!

Twitter announcements vs white paper?

During the preparation of our response to the AI public consultation, we had a moment of confusion. The Government published the white paper and an impact assessment supporting it, which primarily amount to doing nothing and maintaining the status quo (aka AI regulatory gap) in the UK. However, there were increasing reports of the Prime Minister’s change of heart after the emergence of a ‘doomer’ narrative peddled by OpenAI’s CEO and others. At some point, the PM sent out a tweet that made us wonder if the Government was changing policy and the abandoning the approach of the white paper even before the end of the public consultation. This was the tweet.

We could not locate any document describing the ‘Safe strategy of AI’, so the only conclusion we could reach is that the ‘strategy’ was the short twitter threat that followed that first tweet.

It was not only surprising that there was no detail, but also that there was no reference to the white paper or to any other official policy document. We were probably not the only ones confused about it (or so we hope!) as it is in general very confusing to have social media messaging pointing out towards regulatory interventions completely outside the existing frameworks—including live public consultations by the government!

It is also confusing to see multiple different documents make reference to different things, and later documents somehow reframing what previous documents mean.

For example, the announcement of the Foundation Model Taskforce came only a few weeks after the publication of the white paper, but there was no mention of it in the white paper itself. Is it possible that the Government had put together a significant funding package and related policy in under a month? Rather than whether it is possible, the question is why do things in this way? And how mature was the thinking behind the Taskforce?

For example, the initial announcement indicated that

The investment will build the UK’s ‘sovereign’ national capabilities so our public services can benefit from the transformational impact of this type of AI. The Taskforce will focus on opportunities to establish the UK as a world leader in foundation models and their applications across the economy, and acting as a global standard bearer for AI safety.

The funding will be invested by the Foundation Model Taskforce in foundation model infrastructure and public service procurement, to create opportunities for domestic innovation. The first pilots targeting public services are expected to launch in the next six months.

Less than two months later, the announcement of the appointment of the Taskforce chair (below) indicated that

… a key focus for the Taskforce in the coming months will be taking forward cutting-edge safety research in the run up to the first global summit on AI safety to be hosted in the UK later this year.

Bringing together expertise from government, industry and academia, the Taskforce will look at the risks surrounding AI. It will carry out research on AI safety and inform broader work on the development of international guardrails, such as shared safety and security standards and infrastructure, that could be put in place to address the risks.

Is it then a Taskforce and pot of money seeking to develop sovereign capabilities and to pilot public sector AI use, or a Taskforce seeking to develop R&D in AI safety? Can it be both? Is there money for both? Also, why steer the £100m Taskforce in this direction and simultaneously spend £31m in funding an academic-led research centre on ethical and trustworthy AI? Is the latter not encompassing issues of AI safety? How will all of these investments and initiatives be coordinated to avoid duplication of effort or replication of regulatory gaps in the disparate consideration of regulatory issues?

Funding and collaboration opportunities announced via Twitter?

Things can get even more confusing or worrying (for me). Yesterday, the Government put out an official announcement and heavy Twitter-based PR to announce the appointment of the Chair of the Foundation Model Taskforce. This announcement raises a few questions. Why on Sunday? What was the rush? Also, what was the process used to select the Chair, if there was one? I have no questions on the profile and suitability of the appointed Chair (have also not looked at them in detail), but I wonder … even if legally compliant to proceed without a formal process with an open call for expressions of interest, is this appropriate? Is the Government stretching the parallelism with the Vaccines Taskforce too far?

Relatedly, there has been no (or I have been unable to locate) official call for expressions of interest from those seeking to get involved with the Taskforce. However, once more, Twitter seems to have been the (pragmatic?) medium used by the newly appointed Chair of the Taskforce. On Sunday itself, this Twitter thread went out:

I find the last bit particularly shocking. A call for expressions of interest in participating in a project capable of spending up to £100m via Google Forms! (At the time of writing), the form is here and its content is as follows:

I find this approach to AI regulation rather concerning and can also see quite a few ways in which the emerging work approach can lead to breaches of procurement law and subsidies controls, or recruitment processes (depending on whether expressions of interest are corporate or individual). I also wonder what is the rush with all of this and what sort of record-keeping will be kept of all this so that it there is adequate accountability of this expenditure. What is the rush?

Or rather, I know that the rush is simply politically-driven and that this is another way in which public funds are at risk for the wrong reasons. But for the entirely arbitrary deadline of the ‘world AI safety summit’ the PM wants to host in the UK in the Fall — preferably ahead of any general election, I would think — it is almost impossible to justify the change of gear between the ‘do nothing’ AI white paper and the ‘rush everything’ approach driving the Taskforce. I hope we will not end up in another set of enquiries and reports, such as those stemming from the PPE procurement scandal or the ventilator challenge, but it is hard to see how this can all be done in a legally compliant manner, and with the serenity. clarity of view and long-term thinking required of regulatory design. Even in the field of AI. Unavoidably, more to follow.

Procuring AI without understanding it. Way to go?

The UK’s Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF) has published a report on Transparency in the procurement of algorithmic systems (for short, the ‘AI procurement report’). Some of DRCF’s findings in the AI procurement report are astonishing, and should attract significant attention. The one finding that should definitely not go unnoticed is that, according to DRCF, ‘Buyers can lack the technical expertise to effectively scrutinise the [algorithmic systems] they are procuring, whilst vendors may limit the information they share with buyers’ (at 9). While this is not surprising, the ‘normality’ with which this finding is reported evidences the simple fact that, at least in the UK, it is accepted that the AI field is dominated by technology providers, that all institutional buyers are ‘AI consumers’, and that regulators do not seem to see a need to intervene to rebalance the situation.

The report is not specifically about public procurement of AI, but its content is relevant to assessing the conditions surrounding the acquisition of AI by the public sector. First, the report covers algorithmic systems other than AI—that is, automation based on simpler statistical techniques—but the issues it raises can only be more acute in relation to AI than in relation to simpler algorithmic systems (as the report itself highlights, at 9). Second, the report does not make explicit whether the mix of buyers from which it draws evidence includes public as well as private buyers. However, given the public sector’s digital skills gap, there is no reason to believe that the limited knowledge and asymmetries of information documented in the AI procurement report are less acute for public buyers than private buyers.

Moreover, the AI procurement report goes as far as to suggest that public sector procurement is somewhat in a better position than private sector procurement of AI because there are multiple guidelines focusing on public procurement (notably, the Guidelines for AI procurement). Given the shortcomings in those guidelines (see here for earlier analysis), this can hardly provide any comfort.

The AI procurement report evidences that UK (public and private) buyers are procuring AI they do not understand and cannot adequately monitor. This is extremely worrying. The AI procurement report presents evidence gathered by DRCF in two workshops with 23 vendors and buyers of algorithmic systems in Autumn 2022. The evidence base is qualitative and draws from a limited sample, so it may need to be approached with caution. However, its findings are sufficiently worrying as to require a much more robust policy intervention that the proposals in the recently released White Paper ‘AI regulation: a pro-innovation approach’ (for discussion, see here). In this blog post, I summarise the findings of the AI procurement report I find more problematic and link this evidence to the failing attempt at using public procurement to regulate the acquisition of AI by the public sector in the UK.

Misinformed buyers with limited knowledge and no ability to oversee

In its report, DRCF stresses that ‘some buyers lacked understanding of [algorithmic systems] and could struggle to recognise where an algorithmic process had been integrated into a system they were procuring’, and that ‘[t]his issue may be compounded where vendors fail to note that a solution includes AI or its subset, [machine learning]’ (at 9). The report goes on to stress that ‘[w]here buyers have insufficient information about the development or testing of an [algorithmic system], there is a risk that buyers could be deploying an [algorithmic system] that is unlawful or unethical. This risk is particularly acute for high-risk applications of [algorithmic systems], for example where an [algorithmic system] determines a person's access to employment or housing or where the application is in a highly regulated sector such as finance’ (at 10). Needless to say, however, this applies to a much larger set of public sector areas of activity, and the problems are not limited to high-risk applications involving individual rights, but also to those that involve high stakes from a public governance perspective.

Similarly, DRCF stresses that while ‘vendors use a range of performance metrics and testing methods … without appropriate technical expertise or scrutiny, these metrics may give buyers an incomplete picture of the effectiveness of an [algorithmic system]’; ‘vendors [can] share performance metrics that overstate the effectiveness of their [algorithmic system], whilst omitting other metrics which indicate lower effectiveness in other areas. Some vendors raised concerns that their competitors choose the most favourable (i.e., the highest) performance metric to win procurement contracts‘, while ‘not all buyers may have the technical knowledge to understand which performance metrics are most relevant to their procurement decision’ (at 10). This demolishes any hope that buyers facing this type of knowledge gap and asymmetry of information can compare algorithmic systems in a meaningful way.

The issue is further compounded by the lack of standards and metrics. The report stresses this issue: ‘common or standard metrics do not yet exist within industry for the evaluation of [algorithmic systems]. For vendors, this can make it more challenging to provide useful information, and for buyers, this lack of consistency can make it difficult to compare different [algorithmic systems]. Buyers also told us that they would find more detail on the performance of the [algorithmic system] being procured helpful - including across a range of metrics. The development of more consistent performance metrics could also help regulators to better understand how accurate an [algorithmic system] is in a specific context’ (at 11).

Finally, the report also stresses that vendors have every incentive to withhold information from buyers, both because ‘sharing too much technical detail or knowledge could allow buyers to re-develop their product’ and because ‘they remain concerned about revealing commercially sensitive information to buyers’ (at 10). In that context, given the limited knowledge and understanding documented above, it can even be difficult for a buyer to ascertain which information it has not been given.

The DRCF AI procurement report then focuses on mechanisms that could alleviate some of the issues it identifies, such as standardisation, certification and audit mechanisms, as well as AI transparency registers. However, these mechanisms raise significant questions, not only in relation to their practical implementation, but also regarding the continued reliance on the AI industry (and thus, AI vendors) for the development of some of its foundational elements—and crucially, standards and metrics. To a large extent, the AI industry would be setting the benchmark against which their processes, practices and performance is to be measured. Even if a third party is to carry out such benchmarking or compliance analysis in the context of AI audits, the cards can already be stacked against buyers.

Not the way forward for the public sector (in the UK)

The DRCF AI procurement report should give pause to anyone hoping that (public) buyers can drive the process of development and adoption of these technologies. The AI procurement report clearly evidences that buyers with knowledge disadvantages and information asymmetries are at the merci of technology providers—and/or third-party certifiers (in the future). The evidence in the report clearly suggests that this a process driven by technology providers and, more worryingly, that (most) buyers are in no position to critically assess and discipline vendor behaviour.

The question arises why would any buyer acquire and deploy a technology it does not understand and is in no position to adequately assess. But the hype and hard-selling surrounding AI, coupled with its abstract potential to generate significant administrative and operational advantages seem to be too hard to resist, both for private sector entities seeking to gain an edge (or at least not lag behind competitors) in their markets, and by public sector entities faced with AI’s policy irresistibility.

In the public procurement context, the insights from DRCF’s AI procurement report stress that the fundamental imbalance between buyers and vendors of digital technologies undermines the regulatory role that public procurement is expected to play. Only a buyer that had equal or superior technical ability and that managed to force full disclosure of the relevant information from the technology provider would be in a position to (try to) dictate the terms of the acquisition and deployment of the technology, including through the critical assessment and, if needed, modification of emerging technical standards that could well fall short of the public interest embedded in the process of public sector digitalisation—though it would face significant limitations.

This is an ideal to which most public buyers cannot aspire. In fact, in the UK, the position is the reverse and the current approach is to try to facilitate experimentation with digital technologies for public buyers with no knowledge or digital capability whatsoever—see the Crown Commercial Service’s Artificial Intelligence Dynamic Purchasing System (CCS AI DPS), explicitly targeting inexperienced and digitally novice, to put it politely, public buyers by stressing that ‘If you are new to AI you will be able to procure services through a discovery phase, to get an understanding of AI and how it can benefit your organisation’.

Given the evidence in the DRCF AI report, this approach can only inflate the number of public sector buyers at the merci of technology providers. Especially because, while the CCS AI DPS tries to address some issues, such as ethical risks (though the effectiveness of this can also be queried), it makes clear that ‘quality, price and cultural fit (including social value) can be assessed based on individual customer requirements’. With ‘AI quality’ capturing all the problematic issues mentioned above (and, notably, AI performance), the CCS AI DPS is highly problematic.

If nothing else, the DRCF AI procurement report gives further credence to the need to change regulatory tack. Most importantly, the report evidences that there is a very real risk that public sector entities are currently buying AI they do not understand and are in no position to effectively control post-deployment. This risk needs to be addressed if the UK public is to trust the accelerating process of public sector digitalisation. As formulated elsewhere, this calls for a series of policy and regulatory interventions.

Ensuring that the adoption of AI in the public sector operates in the public interest and for the benefit of all citizens requires new legislation supported by a new mechanism of external oversight and enforcement. New legislation is required to impose specific minimum requirements of eg data governance and algorithmic impact assessment and related transparency across the public sector, to address the issue of lack of standards and metrics but without reliance on their development by and within the AI industry. Primary legislation would need to be developed by statutory guidance of a much more detailed and actionable nature than eg the current Guidelines for AI procurement. These developed requirements can then be embedded into public contracts by reference, and thus protect public buyers from vendor standard cherry-picking, as well as providing a clear benchmark against which to assess tenders.

Legislation would also be necessary to create an independent authority—eg an ‘AI in the Public Sector Authority’ (AIPSA)—with powers to enforce those minimum requirements across the public sector. AIPSA is necessary, as oversight of the use of AI in the public sector does not currently fall within the scope of any specific sectoral regulator and the general regulators (such as the Information Commissioner’s Office) lack procurement-specific knowledge. Moreover, units within Cabinet Office (such as the Office for AI or the Central Digital and Data Office) lack the required independence. The primary role of AIPSA would be to constrain the process of adoption of AI by the public sector, especially where the public buyer lacks digital capacity and is thus at risk of capture or overpowering by technological vendors.

In that regard, and until sufficient in-house capability is built to ensure adequate understanding of the technologies being procured (especially in the case of complex AI), and adequate ability to manage digital procurement governance requirements independently, AIPSA would have to approve all projects to develop, procure and deploy AI in the public sector to ensure that they meet the required legislative safeguards in terms of data governance, impact assessment, etc. This approach could progressively be relaxed through eg block exemption mechanisms, once there is sufficiently detailed understanding and guidance on specific AI use cases, and/or in relation to public sector entities that could demonstrate sufficient in-house capability, eg through a mechanism of independent certification in accordance with benchmarks set by AIPSA, or certification by AIPSA itself.

In parallel, it would also be necessary for the Government to develop a clear and sustainably funded strategy to build in-house capability in the public sector, including clear policies on the minimisation of expenditure directed at the engagement of external consultants and the development of guidance on how to ensure the capture and retention of the knowledge developed within outsourced projects (including, but not only, through detailed technical documentation).

None of this features in the recently released White Paper ‘AI regulation: a pro-innovation approach’. However, DRCF’s AI procurement report further evidences that these policy interventions are necessary. Else, the UK will be a jurisdiction where the public sector acquires and deploys technology it does not understand and cannot control. Surely, this is not the way to go.

UK's 'pro-innovation approach' to AI regulation won't do, particularly for public sector digitalisation

Regulating artificial intelligence (AI) has become the challenge of the time. This is a crucial area of regulatory development and there are increasing calls—including from those driving the development of AI—for robust regulatory and governance systems. In this context, more details have now emerged on the UK’s approach to AI regulation.

Swimming against the tide, and seeking to diverge from the EU’s regulatory agenda and the EU AI Act, the UK announced a light-touch ‘pro-innovation approach’ in its July 2022 AI regulation policy paper. In March 2023, the same approach was supported by a Report of the Government Chief Scientific Adviser (the ‘GCSA Report’), and is now further developed in the White Paper ‘AI regulation: a pro-innovation approach’ (the ‘AI WP’). The UK Government has launched a public consultation that will run until 21 June 2023.

Given the relevance of the issue, it can be expected that the public consultation will attract a large volume of submissions, and that the ‘pro-innovation approach’ will be heavily criticised. Indeed, there is an on-going preparatory Parliamentary Inquiry on the Governance of AI that has already collected a wealth of evidence exploring the pros and cons of the regulatory approach outlined there. Moreover, initial reactions eg by the Public Law Project, the Ada Lovelace Institute, or the Royal Statistical Society have been (to different degrees) critical of the lack of regulatory ambition in the AI WP—while, as could be expected, think tanks closely linked to the development of the policy, such as the Alan Turing Institute, have expressed more positive views.

Whether the regulatory approach will shift as a result of the expected pushback is unclear. However, given that the AI WP follows the same deregulatory approach first suggested in 2018 and is strongly politically/policy entrenched—for the UK Government has self-assessed this approach as ‘world leading’ and claims it will ‘turbocharge economic growth’—it is doubtful that much will necessarily change as a result of the public consultation.

That does not mean we should not engage with the public consultation, but the opposite. In the face of the UK Government’s dereliction of duty, or lack of ideas, it is more important than ever that there is a robust pushback against the deregulatory approach being pursued. Especially in the context of public sector digitalisation and the adoption of AI by the public administration and in the provision of public services, where the Government (unsurprisingly) is unwilling to create regulatory safeguards to protect citizens from its own action.

In this blogpost, I sketch my main areas of concern with the ‘pro-innovation approach’ in the GCSA Report and AI WP, which I will further develop for submission to the public consultation, building on earlier views. Feedback and comments would be gratefully received: a.sanchez-graells@bristol.ac.uk.

The ‘pro-innovation approach’ in the GCSA Report — squaring the circle?

In addition to proposals on the intellectual property (IP) regulation of generative AI, the opening up of public sector data, transport-related, or cyber security interventions, the GCSA Report focuses on ‘core’ regulatory and governance issues. The report stresses that regulatory fragmentation is one of the key challenges, as is the difficulty for the public sector in ‘attracting and retaining individuals with relevant skills and talent in a competitive environment with the private sector, especially those with expertise in AI, data analytics, and responsible data governance‘ (at 5). The report also further hints at the need to boost public sector digital capabilities by stressing that ‘the government and regulators should rapidly build capability and know-how to enable them to positively shape regulatory frameworks at the right time‘ (at 13).

Although the rationale is not very clearly stated, to bridge regulatory fragmentation and facilitate the pooling of digital capabilities from across existing regulators, the report makes a central proposal to create a multi-regulator AI sandbox (at 6-8). The report suggests that it could be convened by the Digital Regulatory Cooperation Forum (DRCF)—which brings together four key regulators (the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), Office of Communications (Ofcom), the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA))—and that DRCF should look at ways of ‘bringing in other relevant regulators to encourage join up’ (at 7).

The report recommends that the AI sandbox should operate on the basis of a ‘commitment from the participant regulators to make joined-up decisions on regulations or licences at the end of each sandbox process and a clear feedback loop to inform the design or reform of regulatory frameworks based on the insights gathered. Regulators should also collaborate with standards bodies to consider where standards could act as an alternative or underpin outcome-focused regulation’ (at 7).

Therefore, the AI sandbox would not only be multi-regulator, but also encompass (in some way) standard-setting bodies (presumably UK ones only, though), without issues of public-private interaction in decision-making implying the exercise of regulatory public powers, or issues around regulatory capture and risks of commercial determination, being considered at all. The report in general is extremely industry-orientated, eg in stressing in relation to the overarching pacing problem that ‘for emerging digital technologies, the industry view is clear: there is a greater risk from regulating too early’ (at 5), without this being in any way balanced with clear (non-industry) views that the biggest risk is actually in regulating too late and that we are collectively frog-boiling into a ‘runaway AI’ fiasco.

Moreover, confusingly, despite the fact that the sandbox would be hosted by DRCF (of which the ICO is a leading member), the GCSA Report indicates that the AI sandbox ‘could link closely with the ICO sandbox on personal data applications’ (at 8). The fact that the report is itself unclear as to whether eg AI applications with data protection implications should be subjected to one or two sandboxes, or the extent to which the general AI sandbox would need to be integrated with sectoral sandboxes for non-AI regulatory experimentation, already indicates the complexity and dubious practical viability of the suggested approach.

It is also unclear why multiple sector regulators should be involved in any given iteration of a single AI sandbox where there may be no projects within their regulatory remit and expertise. The alternative approach of having an open or rolling AI sandbox mechanism led by a single AI authority, which would then draw expertise and work in collaboration with the relevant sector regulator as appropriate on a per-project basis, seems preferable. While some DRCF members could be expected to have to participate in a majority of sandbox projects (eg CMA and ICO), others would probably have a much less constant presence (eg Ofcom, or certainly the FCA).

Remarkably, despite this recognition of the functional need for a centralised regulatory approach and a single point of contact (primarily for industry’s convenience), the GCSA Report implicitly supports the 2022 AI regulation policy paper’s approach to not creating an overarching cross-sectoral AI regulator. The GCSA Report tries to create a ‘non-institutionalised centralised regulatory function’, nested under DRCF. In practice, however, implementing the recommendation for a single AI sandbox would create the need for the further development of the governance structures of the DRCF (especially if it was to grow by including many other sectoral regulators), or whichever institution ‘hosted it’, or else risk creating a non-institutional AI regulator with the related difficulties in ensuring accountability. This would add a layer of deregulation to the deregulatory effect that the sandbox itself creates (see eg Ranchordas (2021)).

The GCSA Report seems to try to square the circle of regulatory fragmentation by relying on cooperation as a centralising regulatory device, but it does this solely for the industry’s benefit and convenience, without paying any consideration to the future effectiveness of the regulatory framework. This is hard to understand, given the report’s identification of conflicting regulatory constraints, or in its terminology ‘incentives’: ‘The rewards for regulators to take risks and authorise new and innovative products and applications are not clear-cut, and regulators report that they can struggle to trade off the different objectives covered by their mandates. This can include delivery against safety, competition objectives, or consumer and environmental protection, and can lead to regulator behaviour and decisions that prioritise further minimising risk over supporting innovation and investment. There needs to be an appropriate balance between the assessment of risk and benefit’ (at 5).

This not only frames risk-minimisation as a negative regulatory outcome (and further feeds into the narrative that precautionary regulatory approaches are somehow not legitimate because they run against industry goals—which deserves strong pushback, see eg Kaminski (2022)), but also shows a main gap in the report’s proposal for the single AI sandbox. If each regulator has conflicting constraints, what evidence (if any) is there that collaborative decision-making will reduce, rather than exacerbate, such regulatory clashes? Are decisions meant to be arrived at by majority voting or in any other way expected to deactivate (some or most) regulatory requirements in view of (perceived) gains in relation to other regulatory goals? Why has there been no consideration of eg the problems encountered by concurrency mechanisms in the application of sectoral and competition rules (see eg Dunne (2014), (2020) and (2021)), as an obvious and immediate precedent of the same type of regulatory coordination problems?

The GCSA report also seems to assume that collaboration through the AI sandbox would be resource neutral for participating regulators, whereas it seems reasonable to presume that this additional layer of regulation (even if not institutionalised) would require further resources. And, in any case, there does not seem to be much consideration as to the viability of asking of resource-strapped regulators to create an AI sandbox where they can (easily) be out-skilled and over-powered by industry participants.

In my view, the GCSA Report already points at significant weaknesses in the resistance to creating any new authorities, despite the obvious functional need for centralised regulation, which is one of the main weaknesses, or the single biggest weakness, in the AI WP—as well as in relation to a lack of strategic planning around public sector digital capabilities, despite well-recognised challenges (see eg Committee of Public Accounts (2021)).

The ‘pro-innovation approach’ in the AI WP — a regulatory blackhole, privatisation of ai regulation, or both

The AI WP envisages an ‘innovative approach to AI regulation [that] uses a principles-based framework for regulators to interpret and apply to AI within their remits’ (para 36). It expects the framework to ‘pro-innovation, proportionate, trustworthy, adaptable, clear and collaborative’ (para 37). As will become clear, however, such ‘innovative approach’ solely amounts to the formulation of high-level, broad, open-textured and incommensurable principles to inform a soft law push to the development of regulatory practices aligned with such principles in a highly fragmented and incomplete regulatory landscape.

The regulatory framework would be built on four planks (para 38): [i] an AI definition (paras 39-42); [ii] a context-specific approach (ie a ‘used-based’ approach, rather than a ‘technology-led’ approach, see paras 45-47); [iii] a set of cross-sectoral principles to guide regulator responses to AI risks and opportunities (paras 48-54); and [iv] new central functions to support regulators to deliver the AI regulatory framework (paras 70-73). In reality, though, there will be only two ‘pillars’ of the regulatory framework and they do not involve any new institutions or rules. The AI WP vision thus largely seems to be that AI can be regulated in the UK in a world-leading manner without doing anything much at all.

AI Definition

The UK’s definition of AI will trigger substantive discussions, especially as it seeks to build it around ‘the two characteristics that generate the need for a bespoke regulatory response’: ‘adaptivity’ and ‘autonomy’ (para 39). Discussing the definitional issue is beyond the scope of this post but, on the specific identification of the ‘autonomy’ of AI, it is worth highlighting that this is an arguably flawed regulatory approach to AI (see Soh (2023)).

No new institutions

The AI WP makes clear that the UK Government has no plans to create any new AI regulator, either with a cross-sectoral (eg general AI authority) or sectoral remit (eg an ‘AI in the public sector authority’, as I advocate for). The Ministerial Foreword to the AI WP already stresses that ‘[t]o ensure our regulatory framework is effective, we will leverage the expertise of our world class regulators. They understand the risks in their sectors and are best placed to take a proportionate approach to regulating AI’ (at p2). The AI WP further stresses that ‘[c]reating a new AI-specific, cross-sector regulator would introduce complexity and confusion, undermining and likely conflicting with the work of our existing expert regulators’ (para 47). This however seems to presume that a new cross-sector AI regulator would be unable to coordinate with existing regulators, despite the institutional architecture of the regulatory framework foreseen in the AI WP entirely relying on inter-regulator collaboration (!).

No new rules

There will also not be new legislation underpinning regulatory activity, although the Government claims that the WP AI, ‘alongside empowering regulators to take a lead, [is] also setting expectations‘ (at p3). The AI WP claims to develop a regulatory framework underpinned by five principles to guide and inform the responsible development and use of AI in all sectors of the economy: [i] Safety, security and robustness; [ii] Appropriate transparency and explainability; [iii] Fairness; [iv] Accountability and governance; and [v] Contestability and redress (para 10). However, they will not be put on a statutory footing (initially); ‘the principles will be issued on a non-statutory basis and implemented by existing regulators’ (para 11). While there is some detail on the intended meaning of these principles (see para 52 and Annex A), the principles necessarily lack precision and, worse, there is a conflation of the principles with other (existing) regulatory requirements.

For example, it is surprising that the AI WP describes fairness as implying that ‘AI systems should (sic) not undermine the legal rights of individuals or organisations, discriminate unfairly against individuals or create unfair market outcomes‘ (emphasis added), and stresses the expectation ‘that regulators’ interpretations of fairness will include consideration of compliance with relevant law and regulation’ (para 52). This encapsulates the risks that principles-based AI regulation ends up eroding compliance with and enforcement of current statutory obligations. A principle of AI fairness cannot modify or exclude existing legal obligations, and it should not risk doing so either.

Moreover, the AI WP suggests that, even if the principles are supported by a statutory duty for regulators to have regard to them, ‘while the duty to have due regard would require regulators to demonstrate that they had taken account of the principles, it may be the case that not every regulator will need to introduce measures to implement every principle’ (para 58). This conflates two issues. On the one hand, the need for activity subjected to regulatory supervision to comply with all principles and, on the other, the need for a regulator to take corrective action in relation to any of the principles. It should be clear that regulators have a duty to ensure that all principles are complied with in their regulatory remit, which does not seem to entirely or clearly follow from the weaker duty to have due regard to the principles.

perpetuating regulatory gaps, in particular regarding public sector digitalisation

As a consequence of the lack of creation of new regulators and the absence of new legislation, it is unclear whether the ‘regulatory strategy’ in the AI WP will have any real world effects within existing regulatory frameworks, especially as the most ambitious intervention is to create ‘a statutory duty on regulators requiring them to have due regard to the principles’ (para 12)—but the Government may decide not to introduce it if ‘monitoring of the effectiveness of the initial, non-statutory framework suggests that a statutory duty is unnecessary‘ (para 59).

However, what is already clear that there is no new AI regulation in the horizon despite the fact that the AI WP recognises that ‘some AI risks arise across, or in the gaps between, existing regulatory remits‘ (para 27), that ‘there may be AI-related risks that do not clearly fall within the remits of the UK’s existing regulators’ (para 64), and the obvious and worrying existence of high risks to fundamental rights and values (para 4 and paras 22-25). The AI WP is naïve, to say the least, in setting out that ‘[w]here prioritised risks fall within a gap in the legal landscape, regulators will need to collaborate with government to identify potential actions. This may include identifying iterations to the framework such as changes to regulators’ remits, updates to the Regulators’ Code, or additional legislative intervention’ (para 65).

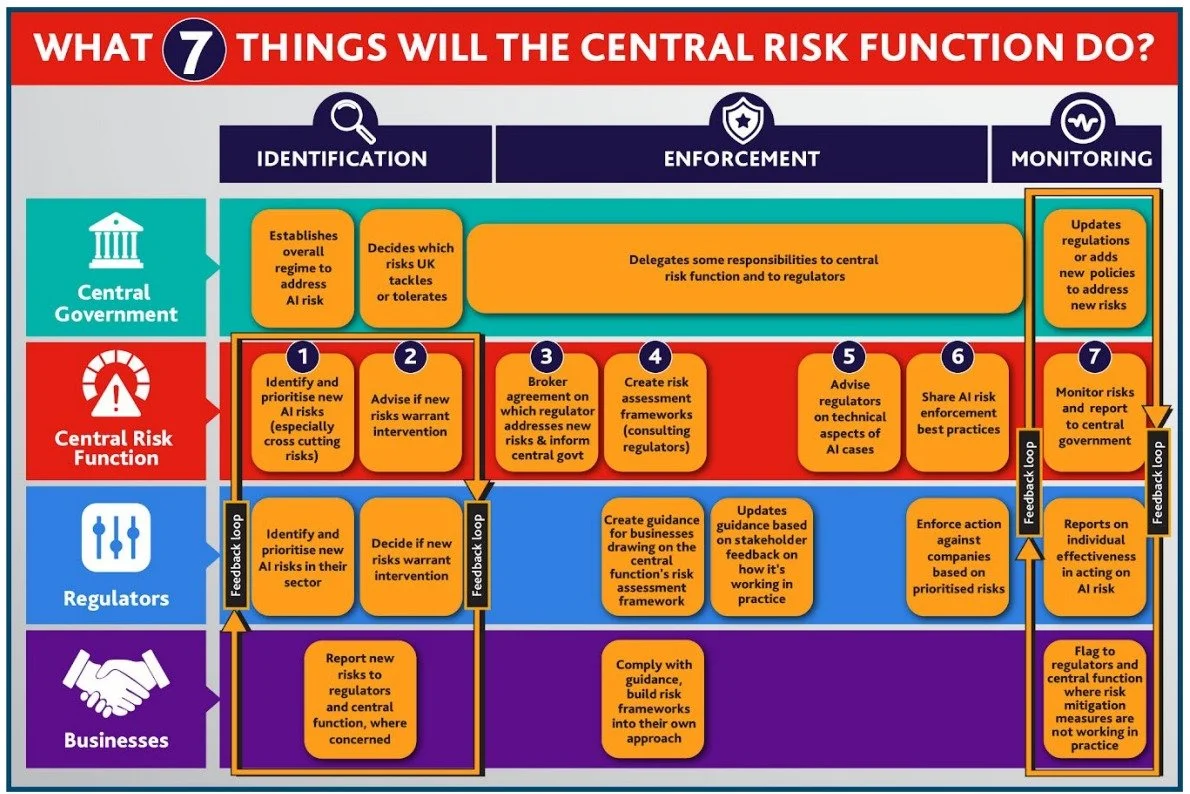

Hoping that such risk identification and gap analysis will take place without assigning specific responsibility for it—and seeking to exempt the Government from such responsibility—seems a bit too much to ask. In fact, this is at odds with the graphic depiction of how the AI WP expects the system to operate. As noted in (1) in the graph below, it is clear that the identification of risks that are cross-cutting or new (unregulated) risks that warrant intervention is assigned to a ‘central risk function’ (more below), not the regulators. Importantly, the AI WP indicates that such central function ‘will be provided from within government’ (para 15 and below). Which then raises two questions: (a) who will have the responsibility to proactively screen for such risks, if anyone, and (b) how has the Government not already taken action to close the gaps it recognises exists in the current legal landscape?

AI WP Figure 2: Central risks function activities.

This perpetuates the current regulatory gaps, in particular in sectors without a regulator or with regulators with very narrow mandates—such as the public sector and, to a large extent, public services. Importantly, this approach does not create any prohibition of impermissible AI uses, nor sets any (workable) set of minimum requirements for the deployment of AI in high-risk uses, specially in the public sector. The contrast with the EU AI Act could not be starker and, in this aspect in particular, UK citizens should be very worried that the UK Government is not committing to any safeguards in the way technology can be used in eg determining access to public services, or by the law enforcement and judicial system. More generally, it is very worrying that the AI WP does not foresee any safeguards in relation to the quickly accelerating digitalisation of the public sector.

Loose central coordination leading to ai regulation privatisation

Remarkably, and in a similar functional disconnect as that of the GCSA Report (above), the decision not to create any new regulator/s (para 15) is taken in the same breath as the AI WP recognises that the small coordination layer within the regulatory architecture proposed in the 2022 AI regulation policy paper (ie, largely, the approach underpinning the DRCF) has been heavily criticised (para 13). The AI WP recognises that ‘the DRCF was not created to support the delivery of all the functions we have identified or the implementation of our proposed regulatory framework for AI’ (para 74).

The AI WP also stresses how ‘[w]hile some regulators already work together to ensure regulatory coherence for AI through formal networks like the AI and digital regulations service in the health sector and the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF), other regulators have limited capacity and access to AI expertise. This creates the risk of inconsistent enforcement across regulators. There is also a risk that some regulators could begin to dominate and interpret the scope of their remit or role more broadly than may have been intended in order to fill perceived gaps in a way that increases incoherence and uncertainty’ (para 29), which points at a strong functional need for a centralised approach to AI regulation.

To try and mitigate those regulatory risks and shortcomings, the AI WP proposes the creation of ‘a number of central support functions’, such as [i} a central monitoring function of overall regulatory framework’s effectiveness and the implementation of the principles; [ii] central risk monitoring and assessment; [iii] horizon scanning; [iv] supporting testbeds and sandboxes; [v] advocacy, education and awareness-raising initiatives; or [vi] promoting interoperability with international regulatory frameworks (para 14, see also para 73). Cryptically, the AI WP indicates that ‘central support functions will initially be provided from within government but will leverage existing activities and expertise from across the broader economy’ (para 15). Quite how this can be effectively done outwith a clearly defined, adequately resourced and durable institutional framework is anybody’s guess. In fact, the AI WP recognises that this approach ‘needs to evolve’ and that Government needs to understand how ‘existing regulatory forums could be expanded to include the full range of regulators‘, what ‘additional expertise government may need’, and the ‘most effective way to convene input from across industry and consumers to ensure a broad range of opinions‘ (para 77).

While the creation of a regulator seems a rather obvious answer to all these questions, the AI WP has rejected it in unequivocal terms. Is the AI WP a U-turn waiting to happen? Is the mention that ‘[a]s we enter a new phase we will review the role of the AI Council and consider how best to engage expertise to support the implementation of the regulatory framework’ (para 78) a placeholder for an imminent project to rejig the AI Council and turn it into an AI regulator? What is the place and role of the Office for AI and the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation in all this?

Moreover, the AI WP indicates that the ‘proposed framework is aligned with, and supplemented by, a variety of tools for trustworthy AI, such as assurance techniques, voluntary guidance and technical standards. Government will promote the use of such tools’ (para 16). Relatedly, the AI WP relies on those mechanisms to avoid addressing issues of accountability across AI life cycle, indicating that ‘[t]ools for trustworthy AI like assurance techniques and technical standards can support supply chain risk management. These tools can also drive the uptake and adoption of AI by building justified trust in these systems, giving users confidence that key AI-related risks have been identified, addressed and mitigated across the supply chain’ (para 84). Those tools are discussed in much more detail in part 4 of the AI WP (paras 106 ff). Annex A also creates a backdoor for technical standards to directly become the operationalisation of the general principles on which the regulatory framework is based, by explicitly identifying standards regulators may want to consider ‘to clarify regulatory guidance and support the implementation of risk treatment measures’.

This approach to the offloading of tricky regulatory issues to the emergence of private-sector led standards is simply an exercise in the transfer of regulatory power to those setting such standards, guidance and assurance techniques and, ultimately, a privatisation of AI regulation.

A different approach to sandboxes and testbeds?

The Government will take forward the GCSA recommendation to establish a regulatory sandbox for AI, which ‘will bring together regulators to support innovators directly and help them get their products to market. The sandbox will also enable us to understand how regulation interacts with new technologies and refine this interaction where necessary’ (p2). This thus is bound to hardwire some of the issues mentioned above in relation to the GCSA proposal, as well as being reflective of the general pro-industry approach of the AI WP, which is obvious in the framing that the regulators are expected to ‘support innovators directly and help them get their products to market’. Industrial policy seems to be shoehorned and mainstreamed across all areas of regulatory activity, at least in relation to AI (but it can then easily bleed into non-AI-related regulatory activities).

While the AI WP indicates the commitment to implement the AI sandbox recommended in the GCSA Report, it is by no means clear that the implementation will be in the way proposed in the report (ie a multi-regulator sandbox nested under DRCF, with an expectation that it would develop a crucial coordination and regulatory centralisation effect). The AI WP indicates that the Government still has to explore ‘what service focus would be most useful to industry’ in relation to AI sandboxes (para 96), but it sets out the intention to ‘focus an initial pilot on a single sector, multiple regulator sandbox’ (para 97), which diverges from the approach in the GCSA Report, which would be that of a sandbox for ‘multiple sectors, multiple regulators’. While the public consultation intends to gather feedback on which industry sector is the most appropriate, I would bet that the financial services sector will be chosen and that the ‘regulatory innovation’ will simply result in some closer cooperation between the ICO and FCA.

Regulator capabilities — ai regulation on a shoestring?

The AI WP turns to the issue of regulator capabilities and stresses that ‘While our approach does not currently involve or anticipate extending any regulator’s remit, regulating AI uses effectively will require many of our regulators to acquire new skills and expertise’ (para 102), and that the Government has ‘identified potential capability gaps among many, but not all, regulators’ (para 103).

To try to (start to) address this fundamental issue in the context of a devolved and decentralised regulatory framework, the AI WP indicates that the Government will explore, for example, whether it is ‘appropriate to establish a common pool of expertise that could establish best practice for supporting innovation through regulatory approaches and make it easier for regulators to work with each other on common issues. An alternative approach would be to explore and facilitate collaborative initiatives between regulators – including, where appropriate, further supporting existing initiatives such as the DRCF – to share skills and expertise’ (para 105).

While the creation of ‘common regulatory capacity’ has been advocated by the Alan Turing Institute, and while this (or inter-regulator secondments, for example) could be a short term fix, it seems that this tries to address the obvious challenge of adequately resourcing regulatory bodies without a medium and long-term strategy to build up the digital capability of the public sector, and to perpetuate the current approach to AI regulation on a shoestring. The governance and organisational implications arising from the creation of common pool of expertise need careful consideration, in particular as some of the likely dysfunctionalities are only marginally smaller than current over-reliance on external consultants, or the ‘salami-slicing’ approach to regulatory and policy interventions that seems to bleed from the ’agile’ management of technological projects into the realm of regulatory activity, which however requires institutional memory and the embedding of knowledge and expertise.