The National Health Service (NHS) has been running a centralised model for health care procurement in England for a few years now. The current system resulted from a redesign of the NHS supply chain that has been operational since 2019 [for details, see A Sanchez-Graells, ‘Centralisation of procurement and supply chain management in the English NHS: some governance and compliance challenges’ (2019) 70(1) NILQ 53-75.]

Given that the main driver for the implementation and redesign of the system was to obtain efficiencies (aka savings) through the exercise of the NHS’ buying power, both the UK’s National Audit Office (NAO) and the House of Commons’ Public Accounts Committee (PAC) are scrutinising the operation of the system in its first few years.

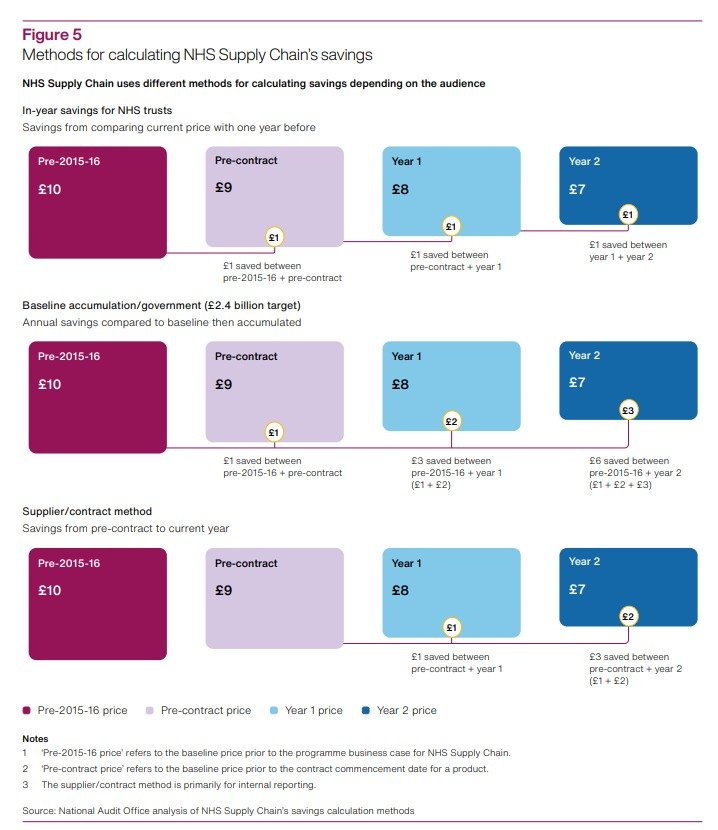

The NAO published a scathing report on 12 January 2024. Among many other concerning issues, the report highlighted how, despite the fundamental importance of measuring savings, ‘NHS Supply Chain has used different methods to report savings to different audiences, which could cause confusion.’ This triggered a clear risk of recounting (ie exaggeration) of claims of savings, as detailed below.

In my submission of written evidence to the PAC Inquiry ‘NHS Supply Chain and efficiencies in procurement’, I look in detail at the potential implications of the use of different savings reporting methods for the (mis)management of scarce NHS resources, should the recounting of savings have allowed private subcontractors to also overclaim savings in order to boost the financial return under their contracts. The full text of my submission is reproduced below, in case of interest.

nao’s findings on recounting of savings

There are three crucial findings in the NAO’s report concerning the use of different (and potentially problematic) savings reporting methods. They are as follows:

DHSC [the Department of Health and Social Care] set Supply Chain a cumulative target of making £2.4 billion savings by 2023-24. Supply Chain told us that it had exceeded this target by the end of 2022-23 although we have not validated this saving. The method for calculating this re-counted savings from each year since 2015-16. Supply Chain calculated its reported savings against the £2.4 billion target by using 2015-16 prices as its baseline. Even if prices had not reduced in any year compared with the year before, a saving was reported as long as prices were lower than that of the baseline year. This method then accumulated savings each year, by adding the difference in price as at the baseline year, for each year. This accumulation continued to re-count savings made in earlier years and did not take inflation into account. For example, if a product cost £10 in 2015-16 and reduced to £9 in 2016-17, Supply Chain would report a saving of £1. If it remained at £9 in 2017-18, Supply Chain would report a total saving of £2 (re-counting the £1 saved in 2016-17). If it then reduced to £8 in 2018-19, Supply Chain would report a total saving of £4 (re-counting the £1 saved in each of 2016-17 and 2017-18 and saving a further £2 in 2018-19) […]. DHSC could not provide us with any original sign-off or agreement that this was how Supply Chain should calculate its savings figure (para 2.4, emphasis added).

Supply Chain has used other methods for calculating savings which could cause confusion. It has used different methods for different audiences, for example, to government, trusts and suppliers (see Figure 5). When reporting progress against its £2.4 billion target it used a baseline from 2015-16 and accumulated the amount each year. To help show the savings that trusts have made individually, it also calculates in-year savings each trust has made using prices paid the previous year as the baseline. In this example, if a trust paid £10 for an item in 2015-16, and then procured it for £9 from Supply Chain in 2016-17 and 2017-18, Supply Chain would report a saving of £1 in the first year and no saving in the second year. These different methods have evolved since Supply Chain was established and there is a rationale for each. Having several methods to calculate savings has the potential to cause confusion (para 2.6, emphasis added).

When I read the report, I thought that the difference between the methods was not only problematic in itself, but also showed that the ‘main method’ for NHS Supply Chain and government to claim savings, in allowing recounting of savings, was likely to have allowed for excessive claims. This is not only a technical or political problem, but also a clear risk of siphoning off NHS scarce budgetary resources, for the reasons detailed below.

Submission to the pac inquiry

00. This brief written submission responds to the call for evidence issued by the Public Accounts Committee in relation to its Inquiry “NHS Supply Chain and efficiencies in procurement”. It focuses on the specific point of ‘Progress in delivering savings for the NHS’. This submission provides further details on the structure and functioning of NHS Supply Chain than those included in the National Audit Office’s report “NHS Supply Chain and efficiencies in procurement” (2023-24, HC 390). The purpose of this further detail is to highlight the broader implications that the potential overclaim of savings generated by NHS Supply Chain may have had in relation to payments made to private providers to whom some of the supply chain functions have been outsourced. It raises some questions that the Committee may want to explore in the context of its Inquiry.

1. NHS Supply Chain operating structure

01. The NAO report analyses the functioning and performance of NHS Supply Chain and SCCL in a holistic manner and without considering details of the complex structure of outsourced functions that underpins the model. This can obscure some of the practical impacts of some of NAO’s findings, in particular in relation with the potential overclaim of savings generated by NHS Supply Chain (paras 2.4, 2.6 and Figure 5 in the report). Approaching the analysis at a deeper level of detail on NHS Supply Chain’s operating structure can shed light on problems with the methods for calculating NHS Supply Chain savings other than the confusion caused by the use of multiple methods, and the potential overclaim of savings in relation to the original target set by DHSC.

02. NHS Supply Chain does not operate as a single entity and SCCL is not the only relevant actor in the operating structure.[1] Crucially, the operating model consists of a complex network of outsourcing contracts around what are called ‘category towers’ of products and services. SCCL coordinates a series of ‘Category Tower Service Providers’ (CTSPs), as listed in the graph below. CTSPs have an active role in developing category management strategies (that is, the ‘go to market approach’ at product level) and heavily influence the procurement strategy for the relevant category, subject to SCCL approval.

03. CTSPs are incentivised to reduce total cost in the system, not just reduce unit prices of the goods and services covered by the relevant category. They hold Guaranteed Maximum Price Target Cost (GMPTC) contracts, under which CTSPs will be paid the operational costs incurred in performing the services against an annual target set out in the contract, but will only make a profit when savings are delivered, on a gainshare basis that is capped.

Source: NHS Supply Chain - New operating model (2018).[2]

04. There are very limited public details on how the relevant targets for financial services have been set and managed throughout the operation of the system. However, it is clear that CTSPs have financial incentives tied to the generation of savings for SCCL. Given that SCCL does not carry out procurement activities without CTSP involvement, it seems plausible that SCCL’s own targets and claimed savings would (primarily) have been the result of the simple aggregation of those of CTSPs. If that is correct, the issues identified in the NAO report may have resulted in financial advantages to CTSPs if they have been allowed to overclaim savings generated.

05. NHS Supply Chain has publicly stated that[3]:

‘Savings are contractual to the CTSPs. As part of the procurement, bidders were asked to provide contractual savings targets for each year. These were assessed and challenged through the process and are core to the commercial model. CTSPs cannot attain their target margins (i.e. profit) unless they are able to achieve contractual savings.’

‘The CTSPs financial reward mechanism [is] based upon a gain share from the delivery of savings. The model includes savings generated across the total system, not just the price of the product. The level of gain share is directly proportional to the level of savings delivered.’

06. In view of this, if CTSPs had been allowed to use a method of savings calculation that re-counted savings in the way NAO details at para 2.4 of its report, it is likely that their financial compensation will have been higher than it should have been under alternative models of savings calculation that did not allow for such re-count. Given the volumes of savings claimed through the period covered by the report, any potential overcompensation could have been significant. As any such overcompensation would have been covered by NHS funding, the Committee may want to include its consideration within its Inquiry and in its evidence-gathering efforts.

__________________________________

[1] For a detailed account, see A Sanchez-Graells, “Centralisation of procurement and supply chain management in the English NHS: some governance and compliance challenges” (2019) 70(1) Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly 53-75.

[2] Available at https://wwwmedia.supplychain.nhs.uk/media/Customer_FAQ_November_2018.pdf (last accessed 12 January 2024).

[3] Ibid, FAQs 24 and 25.