Janet Turra & Cambridge Diversity Fund / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The image features a silver meat grinder. Going into the grinder at the top are various culturally symbolic, historical, and fun icons – such as emojis, old statutes, a computer, newspapers, an aeroplane. At the other end of the meat grinder, coming out is a sea of blue and grey icons representing chat bot responses like 'Let me know if this aligns with your vision' in a grey chat bot message symbol.

The European Commission has published a Factual Summary report on the public consultation on Evaluation of the Public Procurement Directives (the Summary). While we await for the Commission’s fuller analysis of the responses to the consultation (which officials have publicly acknowledged to be processing with AI tools, at least in part) after the summer, it is worth taking a look at the numbers on their face value.

And even before that, it is worth reflecting on the value of a consultation that largely seeks input on the ‘lived experience’ of procurement but sidesteps the critical issue that respondents will provide views based on the specific implementation of the EU rules in their jurisdiction. Barring ‘pure copy-paste’ approaches (such as the good old UK approach), this already creates a significant methodological and analytical hurdle because the underlying reasons for any views expressed cannot without more be attributed to the EU directives—but are rather by necessity mediated by domestic implementation decisions, as well as by domestic procurement culture, legal context and technical infrastructure. The latter is perhaps the easier to grasp. Questions around e-procurement will elicit very different responses depending on the level of functionality, reliability, and sophistication (costs, etc) of e-procurement systems put in place in each of the Member States. Given the broad variation in that regard, it is hard to meaningfully extrapolate the feedback and attribute it to the minimalistic rules on e-procurement in the directives. The same applies across the piece.

Moreover, even setting that aside and taking the statistical summary as provided by the Commission, it is hard to know what to make of it. In short, in my view, the picture that emerges is very much a mixed bag. This further supports the emerging (?) view that the priority should not be the reform of the legal framework, but rather the much more complicated (and expensive) but potentially more impactful work on ensuring procurement practice maximizes use of the flexibility within the existing framework (as discussed in the recent conference held at the University of Copenhagen by Professor Carina Risvig Hamer — see the key conclusions here). Here is why.

(small) majority and (large) minority views

Let’s take a few headline figures and statements:

49% of respondents believe that the Directives did not make the public procurement system flexible enough and 54% think that they did not establish simpler rules for the public procurement system.

most of respondents (48%) think that the rules aiming at increasing procedural flexibility (e. g. the choice of available procedures, time limits for submitting offers, contract modifications) are no longer relevant and adequate.

the same percentage of respondents (48%) consider the Directives’ rules on transparency (e.g. EU-wide publication via Tenders Electronic Daily 'TED') to be still relevant and adequate.

most respondents (53%) believe that the Directives ensure the equal treatment of bidders from other EU countries in all stages of the process and the objective evaluation of tenders.

almost half of respondents (49%) consider that the rules on eProcurement are still relevant and adequate to facilitate market access.

there is some agreement that the Directives’ rules that aim for environmentally friendly procurement (e.g. quality assurance standards and environmental management standards) and for socially responsible procurement (e.g. reserved contracts, requirements on accessibility for people with disabilities and design for all users) are still relevant and adequate. 39% and 43% of respondents say so, respectively.

Most respondents (39%) believe that the objectives of the three Public Procurement Directives are coherent with each other. However, EU legislation relating to public procurement (e.g. sectoral rules such as the Net Zero Industry Act or Clean Vehicles Directive) are not thought to be coherent with the Directives by the largest part of respondents (37% vs 11% who think that sectoral files are coherent).

Most respondents (49%) disagree that the Directives are fit for purpose to contribute to the EU’s strategic autonomy (including the security of EU supply chains). 42% think that the Directives are not fit for purpose in urgent situations. 44% consider that they are not fit for purpose in case of major supply shortages (e.g. supply-chain disruptions during a health, energy or security crisis). 38% think that the Directives do not ensure that security considerations are properly addressed by the contracting authorities.

The figures above, even if phrased in terms of majority of respondents, hardly show a clear majority view on any of those issues. At best, the majoritarian view reaches a figure just above the 50% threshold and, in most instances, the majoritarian view is in reality a large minority view (and sometimes not even that large at all). Constructing the figures to reflect ‘truly’ majority views to potentially influence the direction of reform proposals would require ‘appropriating’ the neutral space (which hovers between 15-28%, depending on the issue in the list above). This raises some questions on methodology itself (should neutral answers be allowed at all?), as well as on ways of treating data that stems from a non-representative and tiny sample (given the figures around number of public buyers, companies tendering for public contracts, and other stakeholders across the EU).

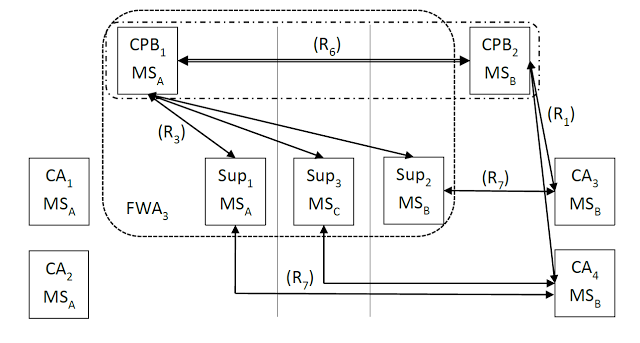

‘Consultation assessment by numbers’ is clearly not going to work. This should push our hopes to the qualitative analysis of the responses, which however raises no smaller questions on the relevance and reliability of the insights provided by this approach to public consultation. Moreover, it can be concerning that the qualitative analysis is being supported by AI tools, as this creates all sort of risks — from technical issues (such as confabulation and the simple making up of ‘insights’) to methodological issues (especially, if the AI is seeking to extract trends, which then largely replicates the problem of ‘assessment by numbers’). It would be very important for the Commission to publish a methodological annex in the future report explaining how AI was used, so that we can have a good sense of whether the qualitative analysis is robust or (use)less.

expert (?) views

To put it mildly, some trends in the Summary run directly against expert insights on the operation (and shortcomings) of the Directives.

This is perhaps most starkly shown in the responses around transparency. There is to my mind no question whatsoever that the expert community considers that there is insufficient procurement transparency and that the TED system is unfit to enable for the collection, publication and facilitation of re-use of procurement data in ways that lead to helpful data insights and, potentially, AI deployment. However, 48% of respondents have said otherwise. What to make of this? What is the point of asking this sort of question in an open consultation? Will this be used as a justification (aham, excuse) not to decidedly revisit the issue of procurement data in a way that promotes the development of an adequate data infrastructure fit for current policy challenges, as the expert community keeps advocating for?

Similarly, though 53% of respondents consider there is no issue of equal treatment of non-domestic bidders, what is the evidence for that? Given how relatively little cross-border tendering there is, on what grounds is this view formed? If the answers are based on a point of principle, what weight (if any) should be given to this set of answers? How does this square up with expert insights (and the Court of Justice’s occasional reminder) that fragmentation of requirements can create de facto unequal treatment (eg where domestic tenderers are more familiar with requirements arising from a broad array of administrative law provisions)?

Jarringly, the outcome of the consultation on the trends in competition for public contracts reflect that: ‘No significant conclusion could be drawn on whether competition had increased, remained the same or decreased over the last 8 years: 25% of respondents think that it decreased, 21% that it remained the same, and 25% that it increased’. However, from the European Court of Auditors’ report, we know that (by available metrics) competition has been on a constant reduction over the last decade. What was the point of asking this question and what to make of this outcome?

sectoral bias

Moreover, the qualitative analysis will require taking into account the specific position (and agenda) of respondents. Clearly, for example, the (declared) perception of aspects of the procurement system will be massively different depending on which side of the policy table respondents sit at.

This is most starkly shown around strategic procurement, where the public/private sector split is clear: ‘Public authorities agree that the Directives have encouraged contracting authorities to buy works, goods and services which are environmentally friendly (56%), socially responsible (55%), and innovative (45%). However, all other respondent groups are less positive. For instance, companies/businesses disagree that the Directives have encouraged contracting authorities to buy works, goods and services which are environmentally friendly (46%), socially responsible (50%), and innovative (54%).’ However, more importantly, and even with problems in the data, we know that uptake of green, social and innovation procurement is woefully low. Again, the European Court of Auditors has clearly documented this. What was the point of asking this question and, more importantly, how will this sort of outcome help inform policy going forward?

What next?

It will be interesting to see what comes out of the fuller analysis of the responses to the public consultation. However, it seems to me that this piece of information gathering will result in a relatively wide variety of views and thus likely have very little meaningful value in informing the direction of travel for the formulation of a proposal for revised rules. More importantly, I think this exercise shows the limited value in trying to obtain this sort of general views on high level questions around issues that are by definition complex, multi-layered, and in some cases politically contested.

As the conclusions to the Copenhagen conference show, there was broad general agreement (in that context) that three elements need to be at the core of the process of review of the EU rules: digitalisation, a clarification of the purpose/s of EU procurement rules, and practical simplification of legal requirements. Given the push to reform, we can hope that the Commission will take a path along those lines going forward. However, the Commission’s own statement of priorities included digitalisation, simplification and EU preference/strategic procurement. That is in itself showing a potentially big clash in approaches and the likely impossibility of achieving a set of goals that cut across each other.

Moreover, I think it is not too late to stop and reconsider whether we are falling in a legocentric trap. During the conference, ‘an element raised several times … was whether it was the procurement rules or the procurement practices that needed to change?’. I think there is a lot value in considering this in detail. We should not delude ourselves thinking that just because something is written in the procurement Directive, reality follows… It would also be helpful to consider whether it is possible to take a staged approach and truly prioritise efforts, so that we can move forward in relation to a single priority (which in my view should be digitalisation) before attempting the more complex and contested aspects of a reform.